That’s not a recession… that’s a recession

The thunder is brewing down under. Here’s why Australia will probably go into recession next year.

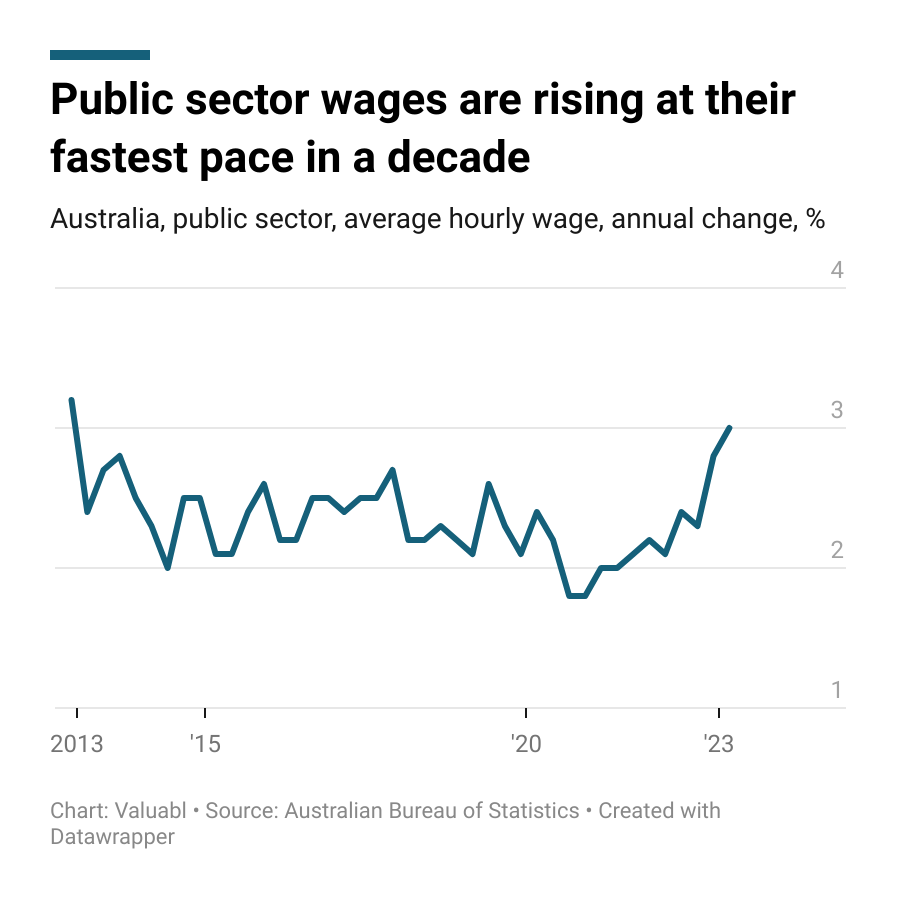

Talking heads refer to Australia as the lucky country. After all, apart from during the pandemic, the country's last recession was in 1992. But the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), the country's central bank, has raised interest rates like mad. Some economists expect a recession is on the way. They're right. Rate hikes and the government's surplus will hurt demand. That comes as public sector wages are rising, slowing inflation's decline.

The Australian government is aiming to run a budgetary surplus this year. Jim Chalmers, the Treasurer, says he expects it to be A$20bn, or 3% of GDP. When the state spends less than it taxes—a surplus—it pulls money out of the private sector. With less money, either spending drops or families and firms borrow more.

But, this time around, people can't borrow much more. Australian families are already some of the most indebted people ever. Household debt is already at a dizzying 112% of GDP, the second highest of any country. Only the Swiss have a greater lust to borrow.

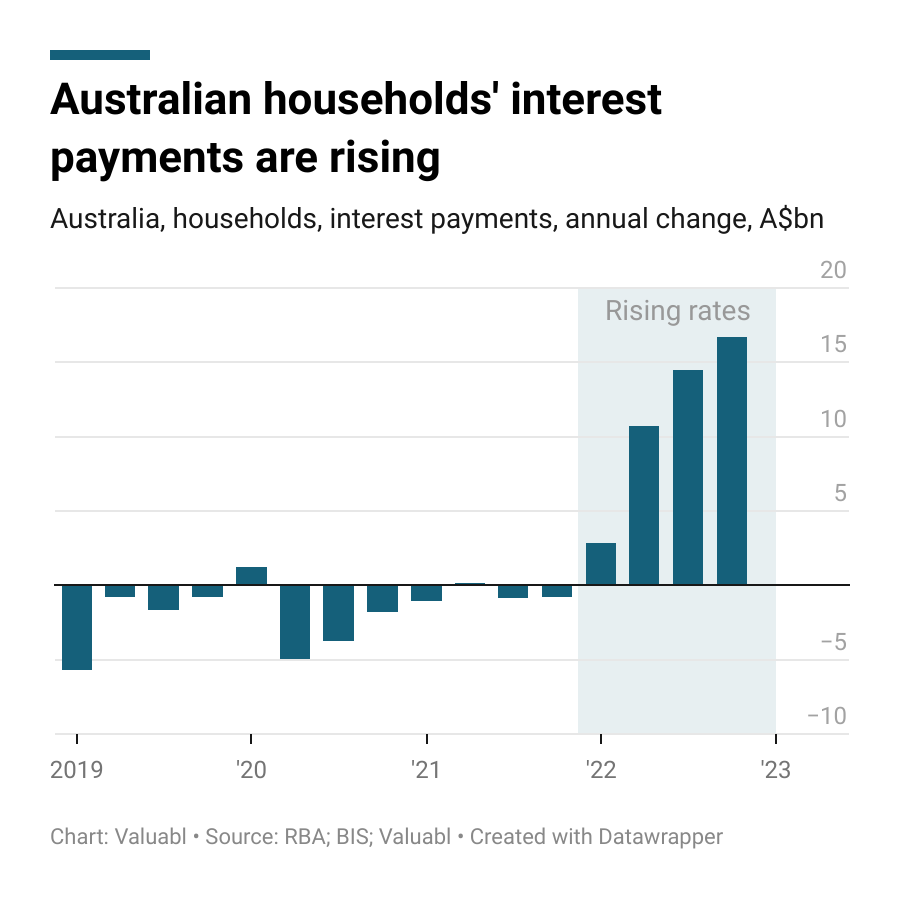

Indeed, recent rate hikes have increased the amount Aussie families spend on interest. Last year, interest payments rose from 5% of disposable household income to 10%. In the past, lower rates more than offset higher levels of household debt. As debt went up, rates went down, and interest payments declined. But, this time around, rates are rising. Families can't afford to borrow more because they already owe so much.

Higher rates make borrowing more costly and will snuff out spending. All else equal, higher interest payments leave families with less money to spend on cars and beer. And when one person spends less, someone else earns less. But interest rates and aggregate demand, the amount spent economy-wide, have a nuanced relationship. While higher rates increase mortgage costs, they also increase the amount the government has to pay.

In America, a country with lots of government debt and fixed-rate mortgages, higher rates increase the government's interest bill more than households'. The state's larger interest expense creates money and pushes it into the economy. Australia, in contrast, has little government debt but lots of household debt. That means rate changes are a more effective lever there. These higher rates have increased the Australian government's interest bill by a paltry 0.8% of GDP. But they've pushed household interest payments by 2.6% of GDP—a 1.8 percentage point difference between them.

The net effect of rate hikes has been to reduce households' borrowing and spending power. Since they already owe so much, higher rates trim the extra amount families can borrow and spend. Economy-wide, the slight increase in the government's interest bill is not enough to offset the increased cost to households.

Public sector employee pay hikes will also stimulate inflation, meaning rates will stay higher for longer. The government has increased public workers' wages by 3% in the past year. That's the most significant raise in a decade.

That is important because the currency's value comes from what you must do to get it. In a fiat economy like Australia, public sector jobs are the primary way the government puts money into the economy. If public sector hourly wages increase, the government pays more for the same thing. That means the government has down-valued the money.

When the government reduces the value of its money, it pushes prices up. As a result, inflation won't fall as fast as it otherwise would have. And since the central bank's only tool for fighting inflation is rates, they'll stay higher for longer and continue to erase demand.

"Well, you see, Aborigines don't own the land. They belong to it. It's like their mother. See those rocks? Been standing there for 600 million years. Still be there when you and I are gone. So arguing over who owns them is like two fleas arguing over who owns the dog they live on." — Michael Dundee