Vol. 2, No. 22

Cost-push inflation can self-correct. The S&P 500 is slightly too expensive. Early disinflationary shoots have sprouted. Value in consumer staples

Welcome to Valuabl, a twice-monthly digital newsletter providing rigorous, value-oriented analysis of the forces shaping global capital markets. New here? Learn more

In today’s issue

Cartoon: Third time’s a smarm

Ideas arena (1 minute)

Hang on, help is on its way (2 minutes)

Cost of capital (3 minutes)

Global stocktake (4 minutes)—Paid subscribers only

Credit creation, cause and effects (6 minutes)—Paid subscribers only

Debt cycle monitor (2 minutes)—Paid subscribers only

Rank and file (2 minutes)—Paid subscribers only

Investment idea (17 minutes)—Paid subscribers only

“Calling someone who trades actively in the market an investor is like calling someone who repeatedly engages in one-night stands a romantic.”

— Warren Buffett

Cartoon: Third time’s a smarm

Ideas arena

Intelligent debate with a global community in subscriber-only discussions.

•••

Top topics from the ideas arena

Hang on, help is on its way

Cost-push inflation can self-correct. By recognising this and giving producers a little more time, our response to inflation need not be so painful.

•••

Cost-push inflation, a type of inflation caused by higher input prices and supply problems, is a dragon that can slay itself. This self-defeat is a slow process, but indeed it happens. Here's how it works and what has occurred so far in this cycle.

When producers raise their prices, this pushes up their top and bottom lines. They get to sell the same amount of stuff but at a higher price. Hence, they make fatter profit margins and returns on capital.

As their projects now generate loftier returns than they used to, these firms are incentivised, and have the means, to reinvest more. They pour capital into starting new projects and maximising the activity of current ones.

These firms ramp up production as much as possible to make as much money as they can. They pump, dig, and build. But as new wells, mines, and factories are big projects that take a long time to finish, output increases in big jumps.

Soon, all these companies produce too much stuff. And, as there is now more than people need, prices drop when they go to sell their goods. The lower prices push down their top and bottom lines, and the cycle is complete.

This cycle's bout of inflation was caused by higher input prices thanks to supply problems. Oil pumpers, food growers, and widget makers couldn't produce as much as we needed. Nor could shippers or lorry drivers get that stuff to where we wanted it. Prices rose.

But relief is on the horizon. Energy, material, and industrial companies worldwide have reinvested greater sums into their businesses. Over the past year, the public companies in these sectors have reinvested $1.1trn and dropped payout ratios to 43% (see: Global stocktake). This reinvestment will spur new production and chill prices. But it will take a little more time.

"Hang on, help is on its way" — Little River Band.

Cost of capital

Interest rates are finance’s most important yet misunderstood prices. Here’s what happened to the cost of money in the past fortnight.

•••

Stock prices rose last fortnight. The S&P 500, an index of big American companies, climbed 7% to 3,821. Investors added $4.3trn to global equity markets (see: Global stocktake) despite the rise in real interest rates. The market bounced off its recent lows but is still down 16% in the past year.

I value the S&P 500 at 3,657, which suggests it is 5% overvalued.

The companies in the index earned $1.8trn after tax in the past year. They paid out $448bn in dividends and $957bn in buybacks and issued $75bn worth of equity. Analysts reckon their earnings will rise to $1.9trn this year and $2trn next.

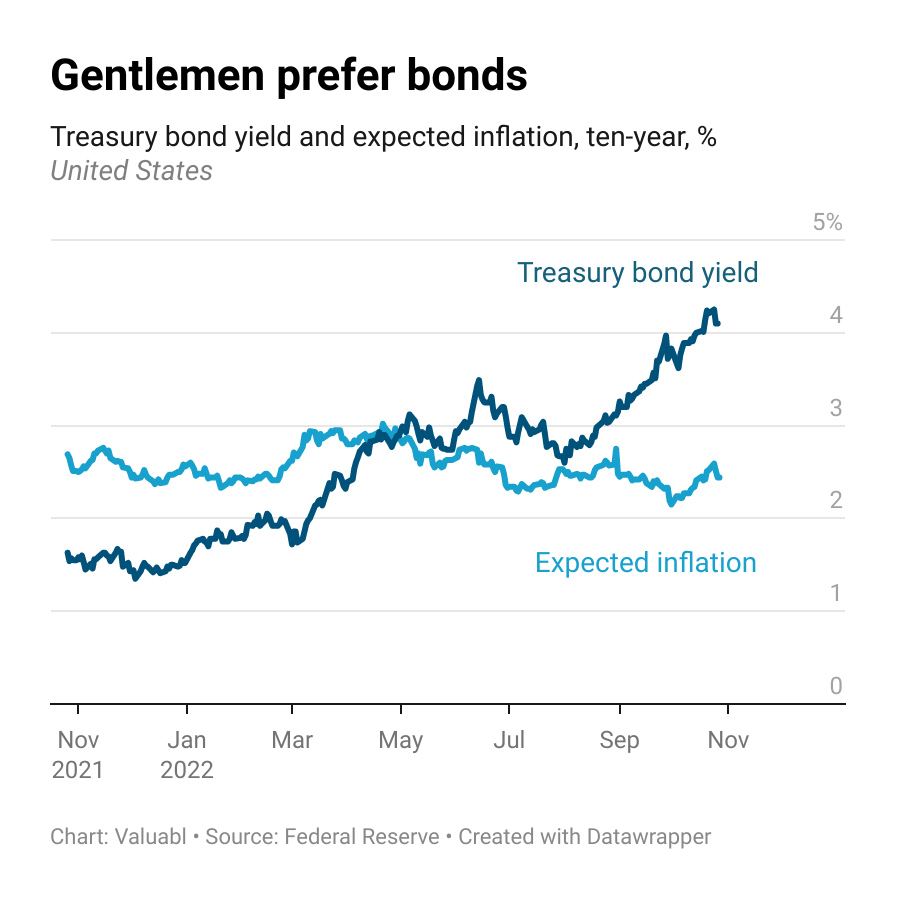

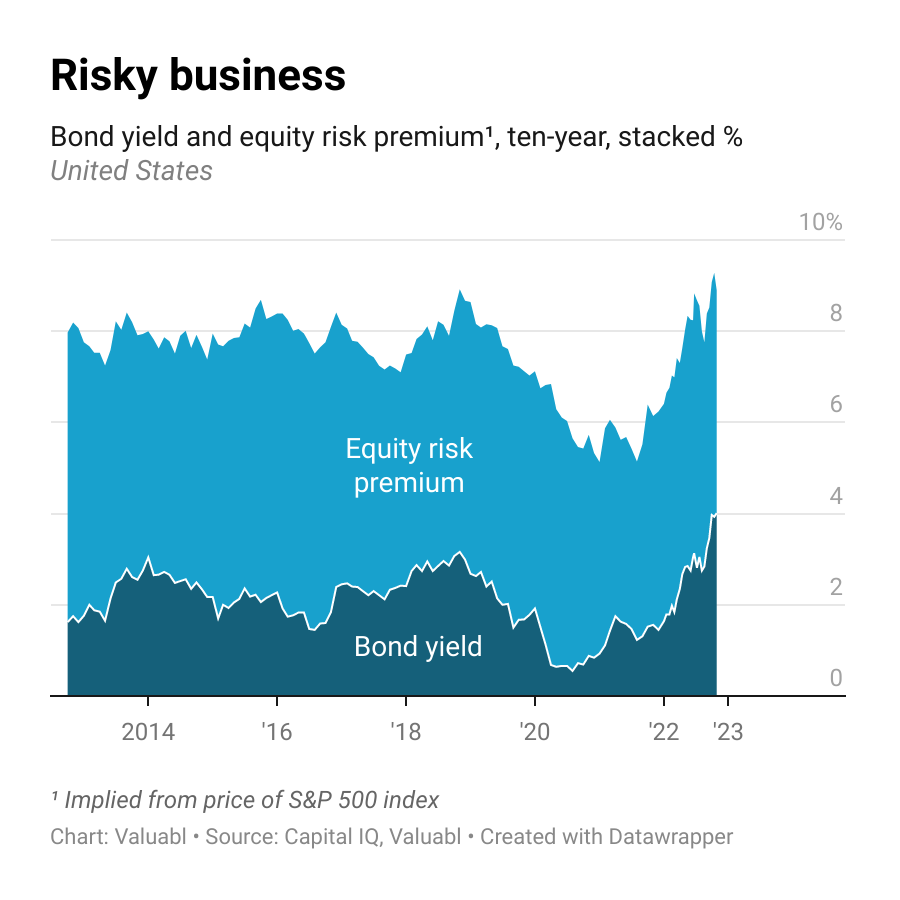

Government bond prices dropped. Yields, which move the opposite way to prices, rose again as inflation expectations did. The yield on a ten-year US Treasury bond, a crucial variable analysts use to value financial assets, rose 19 basis points (bp) to 4.1%. Investors expect inflation to average 2.4% over the next decade, up 15bp from the rate they expected last fortnight.

Hence, the real interest rate, the difference between yields and expected inflation, rose 4bp to 1.7%. These inflation-adjusted rates rose 2.7 percentage points in the past year and are the highest they’ve been since 2010. This has made it more expensive for companies and households who want to refinance.

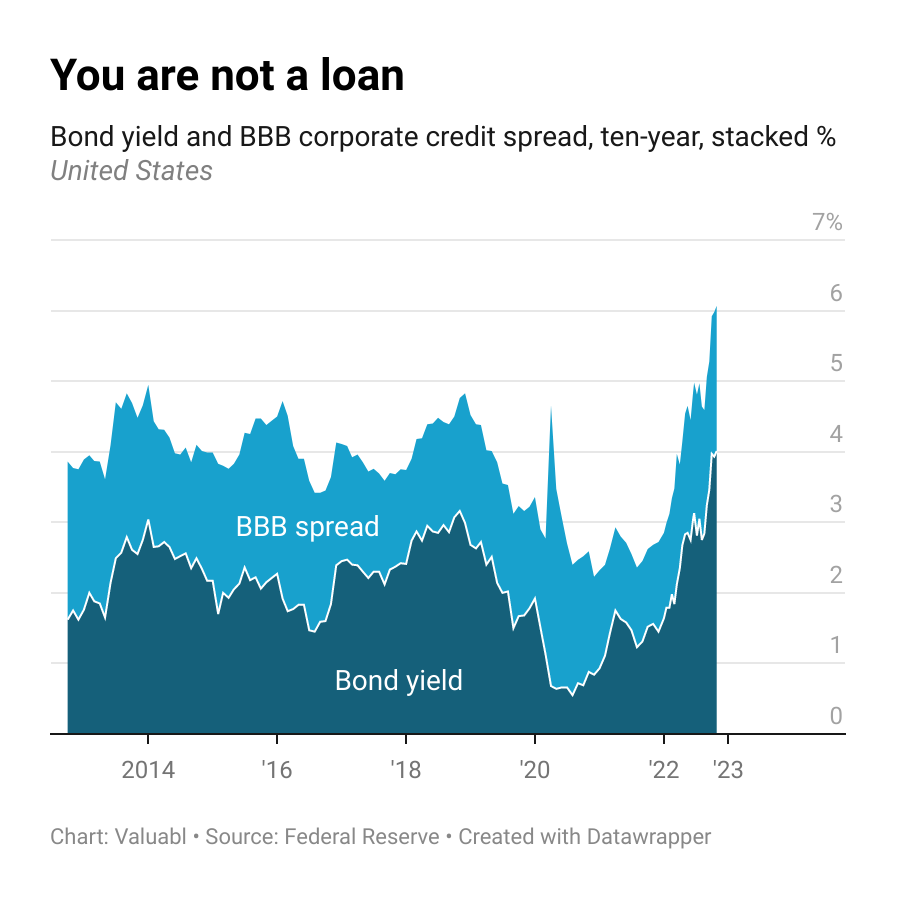

Corporate bond prices also fell. Credit spreads, the extra return creditors demand to lend to businesses instead of the government, dropped 4bp to 2.1%. The spread on these BBB-rated bonds is up 96bp in the past year.

The cost of debt, the annual return lenders expect to make from loans to these companies, rose 15bp to 6.2%. Refinancing costs have more than doubled, up 3.4 percentage points, in the past year. Lenders now charge firms the highest interest rates since 2009. Many firms that came to rely on cheap debt in the past few years won’t survive.

Equity investors are more optimistic than bond traders. The equity risk premium (ERP), the extra return investors demand to buy stocks instead of risk-free bonds, fell 46bp to 4.9%. They’re now 2bp higher than where they were a year ago. Similarly, the cost of equity, the total annual return these investors expect, dropped 27bp to 9%, 2.5 percentage points higher than last year.

Expected equity returns are around the highest level they’ve been since 2012.

Money talks—it just needs an interpreter

You are at the end of the free portion of Valuabl. Become a paid subscriber to access all issues and investment ideas.