Vol. 2, No. 25

Bitcoin won't replace fiat money despite what crypto-nuts say. Stocks look fairly valued. The Treasury owes the Fed how much? And value in kitchen joinery.

Welcome to Valuabl, a twice-monthly digital newsletter providing rigorous, value-oriented analysis of the forces shaping global capital markets. New here? Learn more

In today’s issue

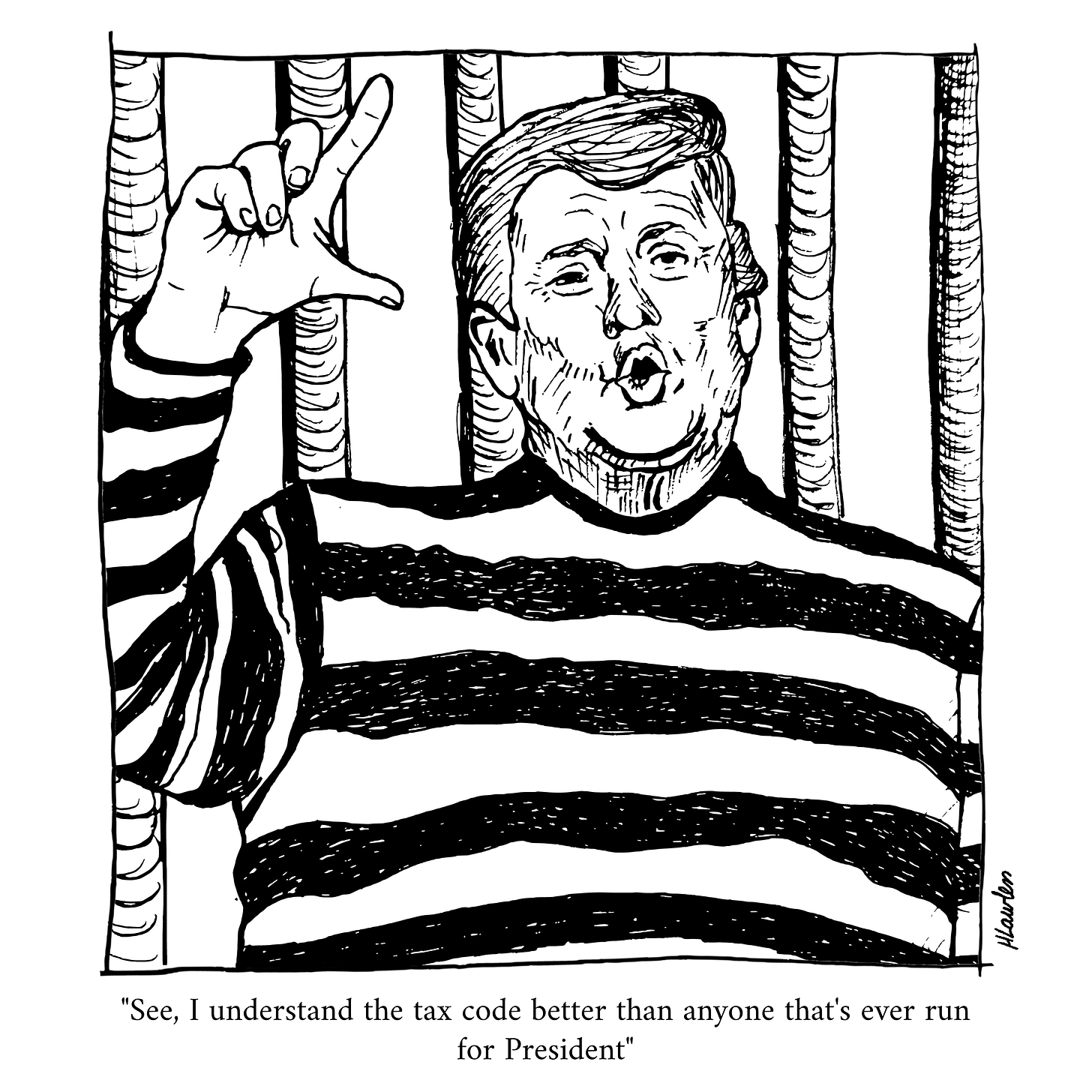

Cartoon: Uncle Sham

Ideas arena

Bitcon: Why satoshis won’t replace fiat (6 minutes)

Cost of capital (3 minutes)

Global stocktake (3 minutes)

Credit creation, cause and effects (6 minutes)

Debt cycle monitor (3 minutes)

Rank and file (2 minutes)

Investment idea (21 minutes)

“You’ve gotta keep control of your time, and you can’t unless you say no. You can’t let people set your agenda in life.”

— Warren Buffett

Cartoon: Uncle Sham

Ideas arena

Intelligent debate with a global community in subscriber-only discussions.

•••

Top topics from the ideas arena

Bitcon: Why satoshis won’t replace fiat

Crypto nuts would have you believe bitcoin is the future of money. Thankfully for everyone with a conscience, it isn’t.

•••

Bitcoin boosters will tell you two things: they’ll say it’s money that’ll eventually replace fiat and that it’s digital gold. The first argument makes no sense to those who understand the monetary system, and the second is so nebulous and vague as to be almost impossible to disprove. It’s a deliberate grift peddled by people who want to see their speculation pay off, even if it’s at the expense of our collective well-being.

There are two main reasons that bitcoin, and its subunits called satoshis, will never replace fiat money properly: First, the government cannot control it and would lose monetary sovereignty, its exclusive control of the currency. Second, bitcoin is deflationary, and its use as money would manifest a deep economic depression.

To comprehend the first point, you must understand the mechanisms through which the state controls and enforces the use of its currency. Those levers are tax liabilities, spending policies, and lawmakers’ legislative authority.

When it creates a tax liability that companies, workers and investors have to pay, the state creates demand for its money. Government money becomes the default medium of exchange as this money is required to measure and settle the tax bill. If economic agents, people or enterprises who make financial decisions, used other exchange mediums, it would be tricky for them to track those transactions in the government’s currency.

Next, the government pays public employees and contractors in its currency. This starts the circular supply and demand system for government money. The state spends its money into the economy, which creates a stock of it. Other economic agents, who need to get that money to settle their tax liabilities to the government, will then exchange for it. This procedure allows the authorities to control how much money is in the economy and where that money goes.

Finally, with legislative authority over the country, the state can mandate that prices and wages are denominated and settled in its currency. The government’s ability to create money and enforce its use gives it monetary sovereignty. This right is necessary to ensure it can generate the funds needed in extreme circumstances like war, famine, or pandemics. Suppose a country that lacked monetary sovereignty was invaded. In that case, it could not create the money it needed to pay for defence. It would become beholden to international creditors who would scalp bitcoin to them at penal interest rates. That would devastate the country.

In that vein, look at the pandemic. If lawmakers couldn’t create the money that paid for furlough schemes and vaccines, millions would have died, and we would have had to rebuild our economies from the rubble. Instead, we have a serious, but not nearly as awful as the alternative, inflationary crisis, which will resolve soon. For the government to function and for the good of our societies, the state must have monetary sovereignty.

The second point is specific to bitcoin: it is deflationary. With an upper limit of 21m coins, regardless of how big the economy or population gets, the supply of bitcoins will always be less than that number. Furthermore, the supply of coins will shrink as people die and their wallets cannot be accessed. If you forget your password, whether through laziness, head trauma, or ill health, your bitcoins, and therefore your money, will be lost to the ether. Suppose this causes the price of bitcoin to increase. In that case, people will be less likely to spend the coins they have and more likely to hoard them. These stashed coins are also effectively removed from the spendable supply.

Economic activity would dry up if countries switched to a deflationary currency. Sure, some necessary exchanges would still happen—people won’t starve themselves to death—but marginal, discretionary purchases would disappear and pull growth down. If spending drops, then so do sales and incomes. Companies get squeezed and earn less. Then they fire workers. Unemployment rises, and people take home less money, so there isn’t as much for them to spend. Aggregate demand drops, and the economy falls into a downward spiral.

Moreover, the cost of capital, the return demanded by lenders and investors to part with their money, would rise to an awful high and productivity gains would disappear. As the available pot of money dwindles, interest rates would increase as people and companies become desperate to borrow or raise equity. Those with bitcoin would lend them out at enormous rates and collect colossal interest payments. The money wouldn’t be invested in new businesses or projects as the return on low-risk loans would be so relatively attractive.

Counter to what bitcon-artists would have you believe, a high bar for investment is bad for society. Instead, the collective hurdle for capital allocation should be low. The more investment happens, the more businesses and innovations we try. That makes breakthrough technology more likely and improves productivity and our prosperity.

Under a bitcoin standard, satoshis would beget more satoshis without any productive application. And everyone would be poorer. The con is on.

Cost of capital

Interest rates are finance’s most important yet misunderstood prices. Here’s what happened to the cost of money in the past fortnight.

•••

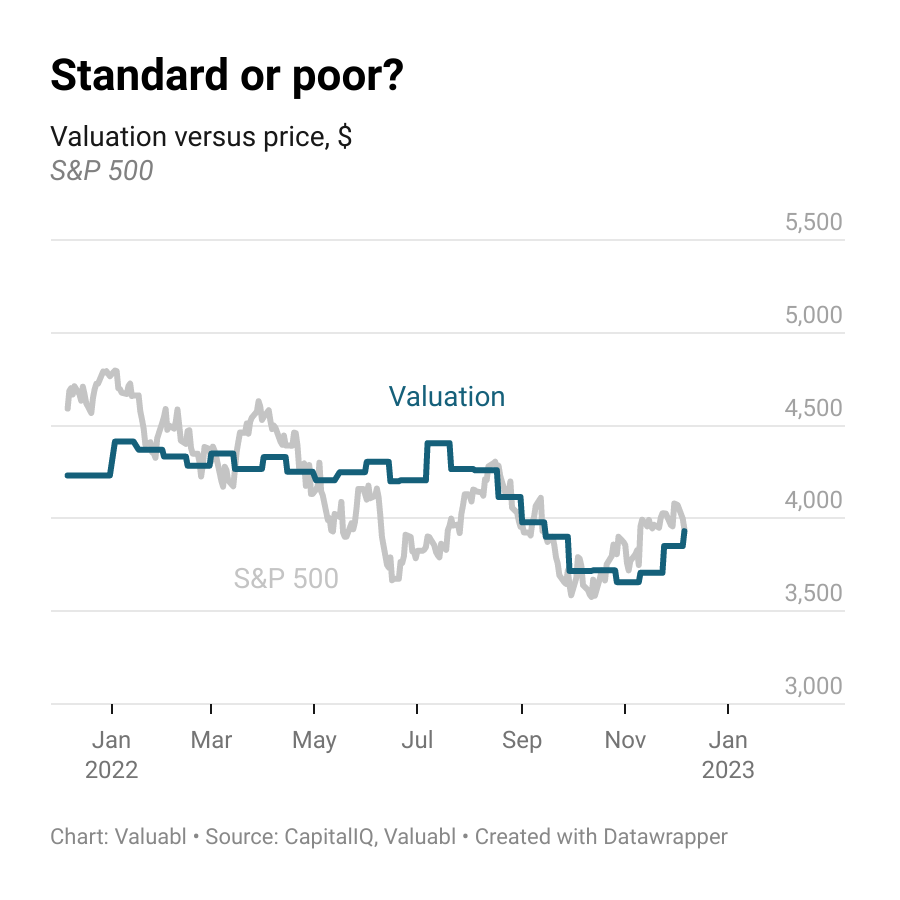

Stock prices fell last fortnight. The S&P 500, an index of big American companies, dropped 2% to 3,941. But investors added $4trn to global equity markets (see: Global stocktake) as inflation-adjusted interest rates fell. The market has bounced back from its recent lows but is still down 14% in the past year.

I value the S&P 500 at 3,931, which suggests it is fairly valued.

The companies in the index earned $1.8trn after tax in the past year. They paid out $507bn in dividends and $1,047bn in buybacks and issued $74bn worth of equity. Analysts reckon their earnings will rise to $1.9trn this year and $2trn next.

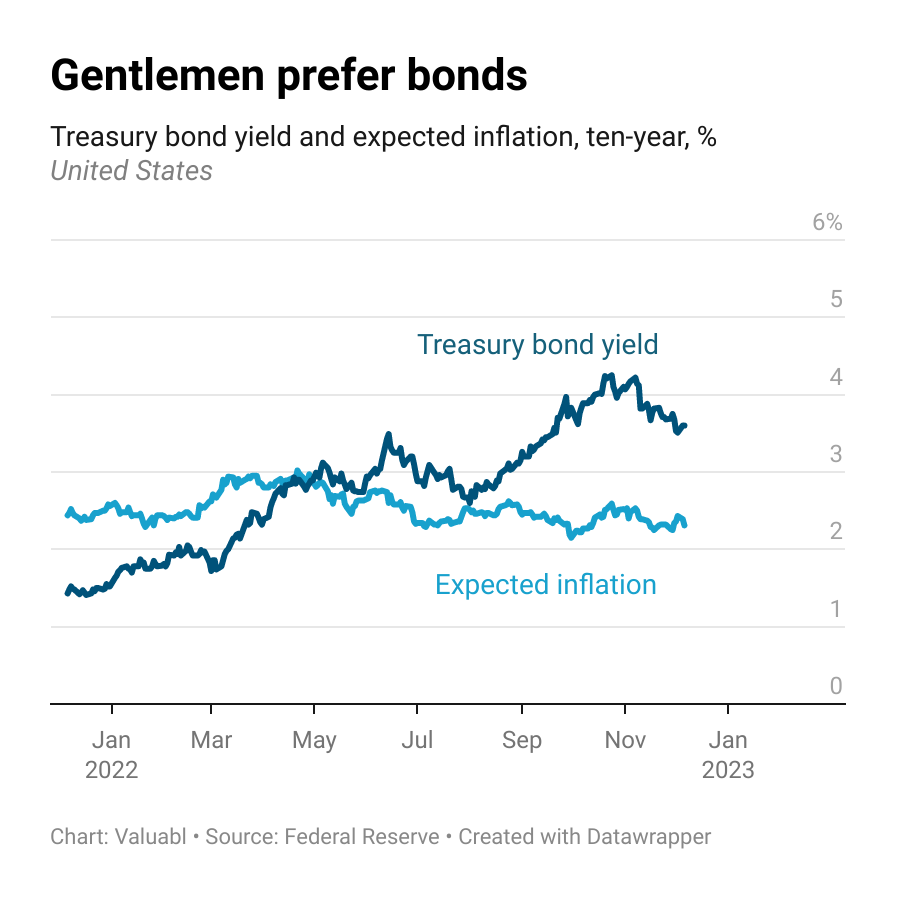

Government bond prices rose. Yields, which move the opposite way to prices, dropped again as inflation expectations fell. The yield on a ten-year US Treasury bond, a critical variable analysts use to value financial assets, fell 16 basis points (bp) to 3.6%. Investors expect inflation to average 2.3% over the next decade, down 1bp from the rate they expected last fortnight.

Hence, the real interest rate, the difference between yields and expected inflation, dropped 15bp to 1.3%. These inflation-adjusted rates rose 2.3 percentage points in the past year.

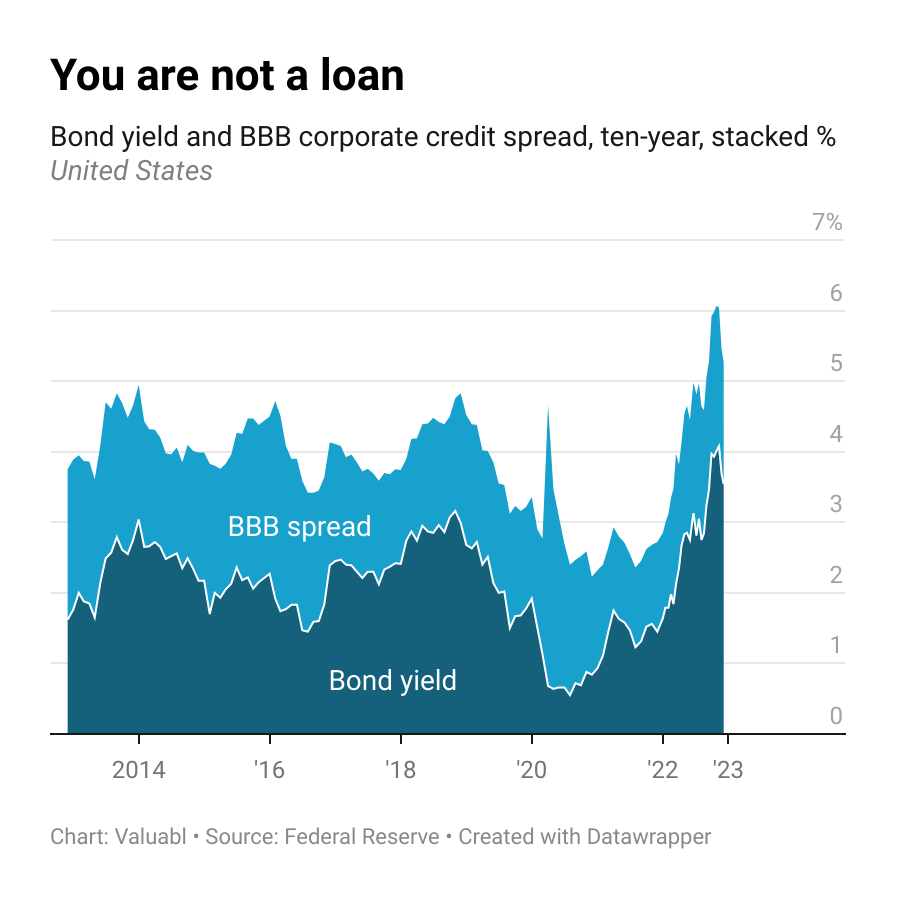

Corporate bond prices also rose. Credit spreads, the extra return creditors demand to lend to businesses instead of the government, dropped 4bp to 1.7%. The spread on these BBB-rated bonds is up 48bp in the past year.

The cost of debt, the annual return lenders expect when lending to these companies, dropped 20bp to 5.3%. Refinancing costs have almost doubled, up 2.7 percentage points, in the past year. Lenders now charge firms about the highest interest rates since 2009. But these rates are on track to return to their long-term average.

The equity risk premium (ERP), the extra return investors demand to buy stocks instead of risk-free bonds, rose 4bp to 5.1%. They’re now just 32bp higher than where they were a year ago. In contrast, the cost of equity, the total annual return these investors expect, fell 12bp to 8.7%, 2.5 percentage points higher than last year. These expected returns are also in line with the long-term average.

Now that capital costs have normalised and hover around their long-term averages, stock market movements should be driven by earnings expectations. I will watch closely how these evolve over the next few months.

Money talks—it just needs an interpreter

You are at the end of the free portion of Valuabl. Become a paid subscriber to access all issues and investment ideas.