Vol. 3, No. 2 — Starch raving mad

A global potato shortage will keep chip prices high. A fall in bond yields helped prop up equity valuations. Greek stocks look cheap. America's housing affordability crisis. Value in cork production.

Welcome to Valuabl, a twice-monthly digital newsletter providing rigorous, value-oriented analysis of the forces shaping global capital markets. New here? Learn more

In today’s issue

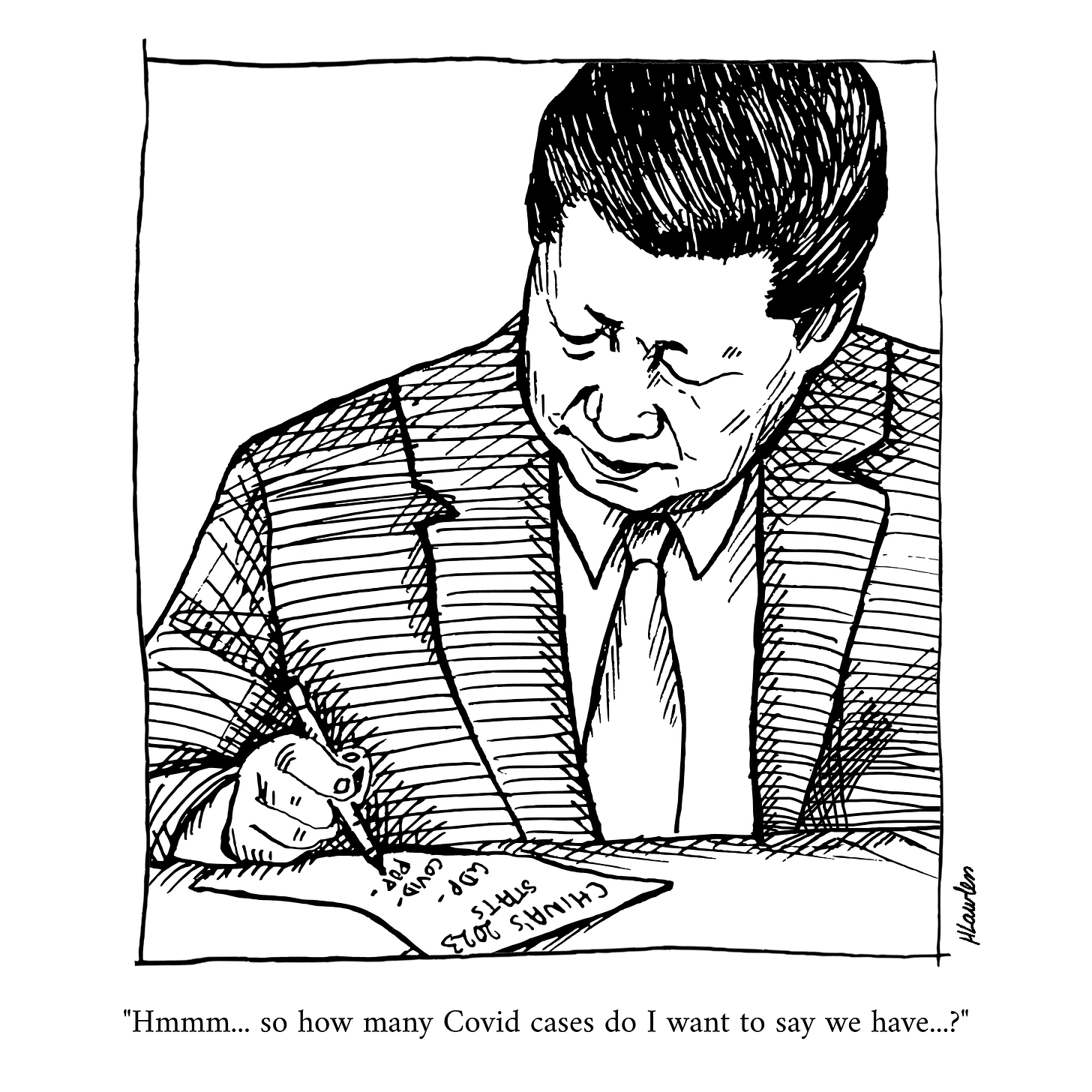

Cartoon: Chliena

Ideas arena

Starch raving mad (3 minutes)

Cost of capital (3 minutes)

Global stocktake (4 minutes)

Rank and file (1 minute)

Credit creation, cause and effects (8 minutes)

Debt cycle monitor (2 minutes)

Investment idea (22 minutes)

“In the faculty of writing nonsense, stupidity is no match for genius.” — Walter Bagehot

Cartoon: Chliena

Ideas arena

Intelligent debate with a global community in subscriber-only discussions.

•••

Top topics from the ideas arena

Starch raving mad

Bad weather and lousy policies have made spud prices shoot up—much to the chagrin of chip crunchers and mash munchers.

•••

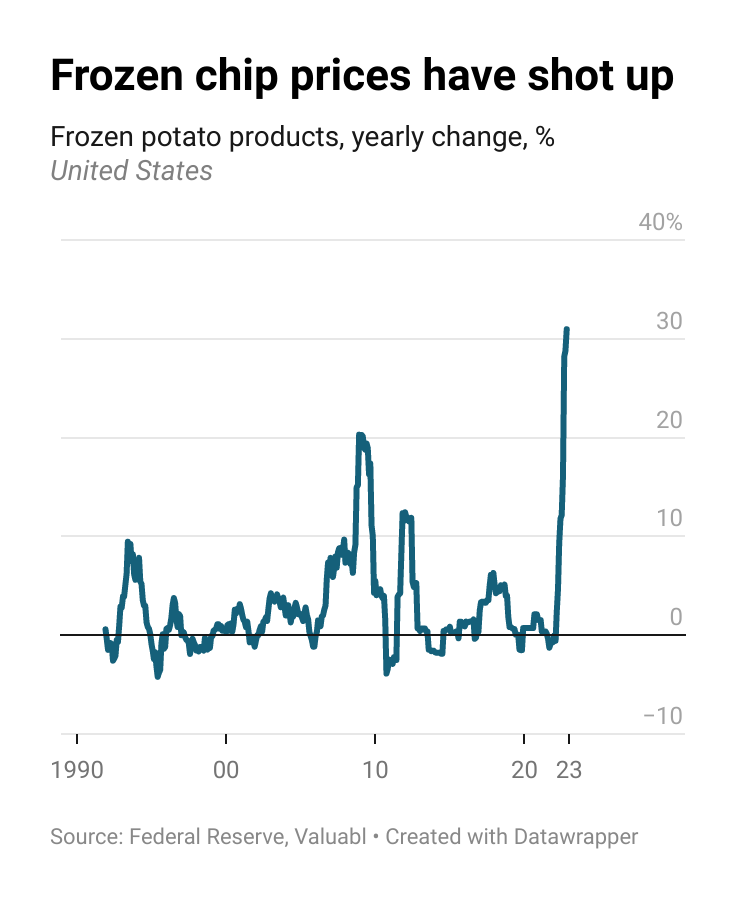

Chip prices have lept amid a global potato shortage. Spuds, which cooks turn into chips and mash, are in short supply because of bad weather, war and lockdowns. As a result, the price of potatoes and their derivatives have gone up everywhere. In America, a 16oz (454g) bag of salty gut-growing potato chips costs 22% more than last year, while frozen fry prices are up by almost a third, the fastest jump on record.

Inclement weather and supply-chain problems across the potato-growing parts of the world are to blame. Local spud supplies have been hammered, and the importable stock has dwindled.

In Australia, a country that imports over a quarter of the potatoes eaten, Woolworths, a supermarket chain, has introduced a purchase limit on frozen potato products. They warned prices might rise by up to a third as the long wet season meant farmers struggled to plant and harvest potato crops. Wholesale prices are up 25%.

Katherine Myers, a leader of the Victorian Farmers Federation, a lobby group, reckons that the country’s big potato companies would usually plan to bring in more spuds from Europe but “the surplus hasn’t been there this year.” A confluence of anti-potato forces has hit the world’s top potato-growing countries.

Chinese farmers, who harvested 22% of the world’s supply in 2020, have endured zero-covid policies which smashed supply chains. India has had horrible floods. Russia’s invasion hit Ukrainian potato production as farmers fled, fertiliser costs rose, and fewer seeds were planted. And the North West of America, the prime potato-growing part of the United States, has been hit by a heatwave and droughts.

Ms Myers said she expected the shortage of frozen chips to continue throughout the year. “We’re really not likely to see good potato yields returning in the next 12 months,” she said.

Summer and Autumn are usually potato-cultivating seasons. But with Autumn fast approaching in the Southern hemisphere and supplies already short, there is little chance of catching up this year. While Northern countries won’t be able to build back their tactical tater reserves until the second half of the year.

“What I say is that, if a man really likes potatoes, he must be a pretty decent sort of fellow.” ― A. A. Milne

Cost of capital

Finance’s most important yet misunderstood price is capital. Here’s what happened to the cost of money in the past fortnight.

•••

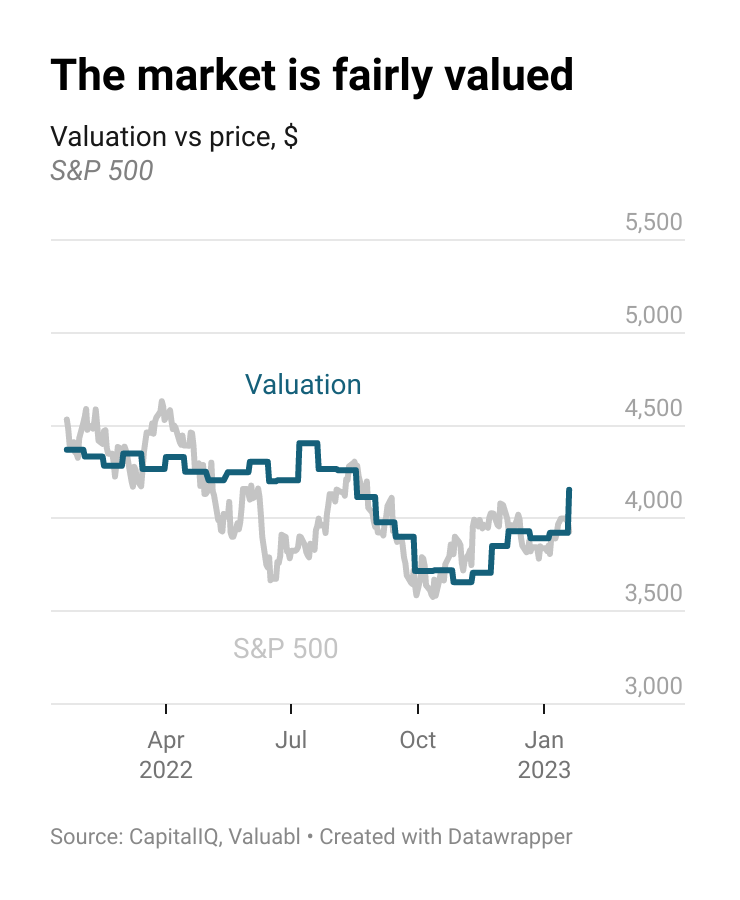

Stock prices rose last fortnight. The S&P 500, an index of big American companies, climbed 4% to 3,991. The market has bounced back from its October lows but is still down 13% in the past year. I value the S&P 500 at 4,154, which suggests it is 6% undervalued.

The companies in the index earned $1.8trn after tax in the past year. They paid out $499bn in dividends and $981bn in buybacks, and issued $69bn worth of equity.

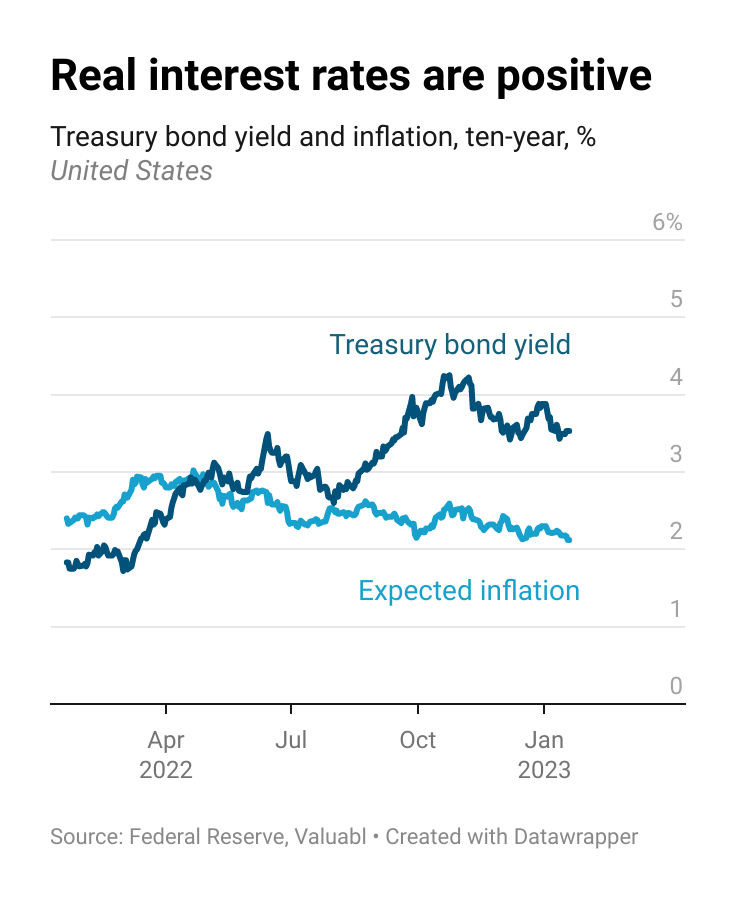

Government bond prices rose. Yields, which move the opposite way to prices, fell as inflation expectations did. The yield on a ten-year US Treasury bond, a critical variable analysts use to value financial assets, dropped 16 basis points (bp) to 3.5%. Investors expect inflation to average 2.1% over the next decade, down 10bp from the rate they expected last fortnight.

Hence, the real interest rate, the difference between yields and expected inflation, declined 6bp to 1.4%. These inflation-adjusted rates are up two percentage points in the past year.

Corporate bond prices also went up. Credit spreads, the extra return creditors demand to lend to businesses instead of the government, fell by 13bp to 1.6%. The spread on these BBB-rated bonds is up 39bp in the past year.

The cost of debt, the annual return lenders expect when lending to these companies, collapsed by 29bp to 5.1%. Refinancing costs have almost doubled, up 2.1 percentage points, in the past year. Lenders now charge firms about the highest interest rates since 2009.

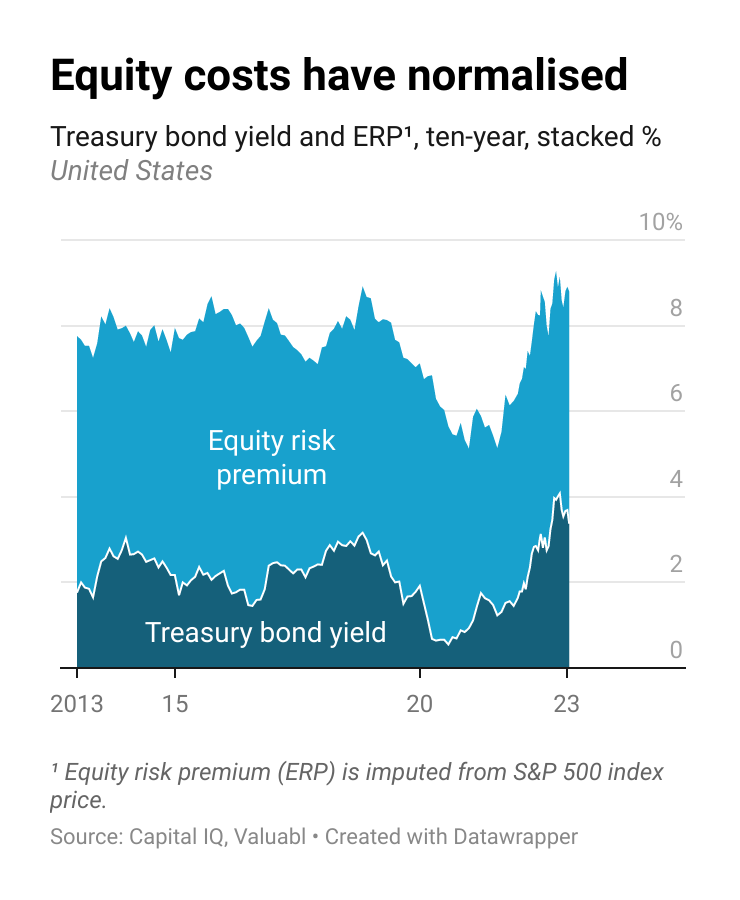

The equity risk premium (ERP), the extra return investors demand to buy stocks instead of risk-free bonds, rose 21bp to 5.4%. It’s now 57bp higher than where it was a year ago. In addition, the cost of equity, the total annual return these investors expect, rose 5bp to 9%, 2.2 percentage points higher than last year. These expected returns are also roughly in line with the long-term average.

Money talks—it just needs an interpreter

You are at the end of the free portion of Valuabl. Become a paid subscriber to access all issues and investment ideas.