Vol. 3, No. 7 — Banking on bargains

Bargains amongst regional American bank stocks. Markets have calmed down a bit. Energy firms are reinvesting like mad. No recession in sight. Value in cereal.

Welcome to Valuabl, a twice-monthly digital newsletter providing value-oriented financial market analysis and investment ideas. Learn more

In today’s issue

Cartoon: Too big to fail

Banking on bargains—are lenders cheap yet? (7 minutes)

Cost of capital (3 minutes)

Global stocktake (2 minutes)

Rank and file (1 minute)

Credit creation, cause and effects (6 minutes)

Debt cycle monitor (1 minute)

Investment idea (15 minutes)

"It's not a complicated business. You buy low and sell high." — Walter Schloss

Cartoon: Too big to fail

Banking on bargains—are lenders cheap yet?

Recent financial market turmoil has pushed banks' share prices down. No doubt a lot of it is justifiable. But, amongst the rubble, investors should be able to find some bargains.

•••

It's been a shocking month for banks. A few weeks ago, analysts were sure the economy was powering full steam ahead. Now they're worried the fallout from Silicon Valley Bank's demise will cause a deep recession. It's not only an American problem, however. Over in Europe, Swiss authorities sold Credit Suisse, one of the country's oldest institutions, to UBS, another big lender. Unsurprisingly, bank stocks have fallen amongst the carnage.

The KBW index, a tracker of American bank stocks, has fallen 27% over the last three weeks. That raises the question: are bank stocks cheap yet? My research suggests that regional American banks are inexpensive if the current batch of problems doesn't kill them. But large banks will have to fall further before they become interesting.

America's banking market has significant upside from current prices

Overall, the banking industry is cheap. All 550-ish public American banks are worth between $1.8trn and $2trn. That's a 32% upside from the current $1.5trn market cap. Moreover, Monte Carlo simulation, a statistical scenario analysis, suggests current prices are below the 20th percentile of potential values. Or, put another way, there's a one-in-five chance bank stocks are expensive.

The sector as a whole is stunningly profitable. Last year, American banks made $160bn of profit on $1.4trn of equity—an 11% return. Of that profit, they paid out $57bn, or 36%, to shareholders. Consequently, industry profits should grow by 7% this year. But investors reckon the opposite will happen. They've priced bank earnings to drop 2% this year and next.

Investors are nervous that interest rate rises might kick off a stream of defaults, causing bank earnings to fall. They're also wary that depositors, spooked by the run on SVB, might empty their accounts. Bank-run contagion would push small banks to the edge unless lawmakers stepped in again to guarantee deposits. Liquidity problems and higher default rates would weigh on earnings, especially with lower bond prices. That and higher capital costs would slash valuations.

Still, interest rate rises will also help bank profits. Their net interest margins, the gap between the rates banks borrow and lend at, will rise. Banks are quick to raise the rates they charge but slow to raise the rates they pay. That will boost bottom lines, potentially offsetting defaults. Unless there are immense regulatory or interest rate shocks, the banking market, as a whole, is cheap.

Searching for bargains: regional banks versus money centres

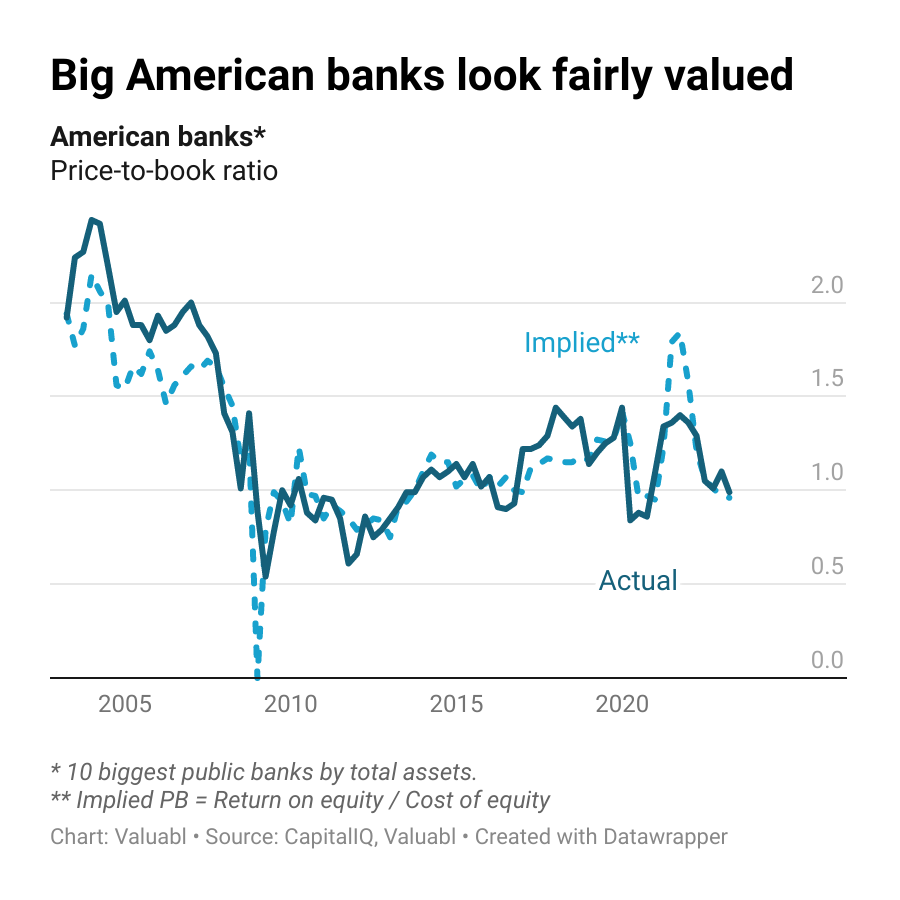

Although the entire industry looks undervalued, the large end of the market doesn't seem cheap. Big money centre banks like JPMorgan and Bank of America trade at a fair price based on their price-to-book (PB) ratios. Currently, the ten largest banks by assets managed have an average PB ratio of one, almost exactly where it should be.

Bank investors typically value banks based on the ratio of their return on equity (ROE) to their cost of equity. Banks that earn a lot of profit per dollar of equity will be worth more than banks that don't. Similarly, banks with a higher equity cost will be worth less than those with a lower one.

The ratios for the big banks have moved around a lot over the last couple of decades. Returns on equity fell during the global financial crisis (GFC) and haven't recovered. Lawmakers forced banks to hold more capital and focus on safer loans. Earning excess profits became harder. Since then, big lenders have made a meagre 8% return on their equity capital—the same as that capital's cost.

The big banks are much more capital-intensive than they used to be. These days, more equity must be reinvested for them to grow because loans generate less revenue at low-interest rates than high ones. As rates dropped, banks had to do bigger loans to move the needle. That meant more equity had to be retained, and returns fell. Consequently, investors haven't been willing to pay the lavish multiples they used to.

But, if interest rates keep increasing, banks' capital efficiency could improve. Higher rates would beget higher revenues. And more revenue per dollar of shareholders' equity would, in turn, push ROEs and PB multiples up. Still, even at higher rates, improvements in the capital efficiency of these big banks is capped. After SVB's collapse, regulators must be itching to roll out new red tape to restrict what banks can and can't do. New laws will probably tell banks to hold even more capital and narrow the scope of lending. This, in turn, will hamper capital efficiency gains.

Learning from the last crisis

For the industry to be cheap as a whole while the big banks aren't, there must be bargains amongst the smaller regional banks. Bank opaqueness and complexity puts-off many investors. Orthodoxy amongst traders is that small banks won't get bailed out, while big ones will. That makes them seem like a riskier bet. Still, small regional banks are likely a lush hunting ground for savvy investors.

Coming out of the GFC, investors who could buy banks during periods of panic did well. In September 2008, Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett's conglomerate, invested $5bn in Goldman Sachs. Berkshire got preferred shares with a 10% annual dividend and options to buy 43m shares. By 2013, five years later, the investment had made a $3.3bn profit.

You're not The Oracle. Nor am I. And the banking system is not as distressed as it was then. But, with the right approach and a keen eye for opportunity, investors can spot lucrative deals, just as Buffett did then.

Cost of capital

Finance’s most important yet misunderstood price is capital. Here’s what happened to the cost of money in the past fortnight.

•••

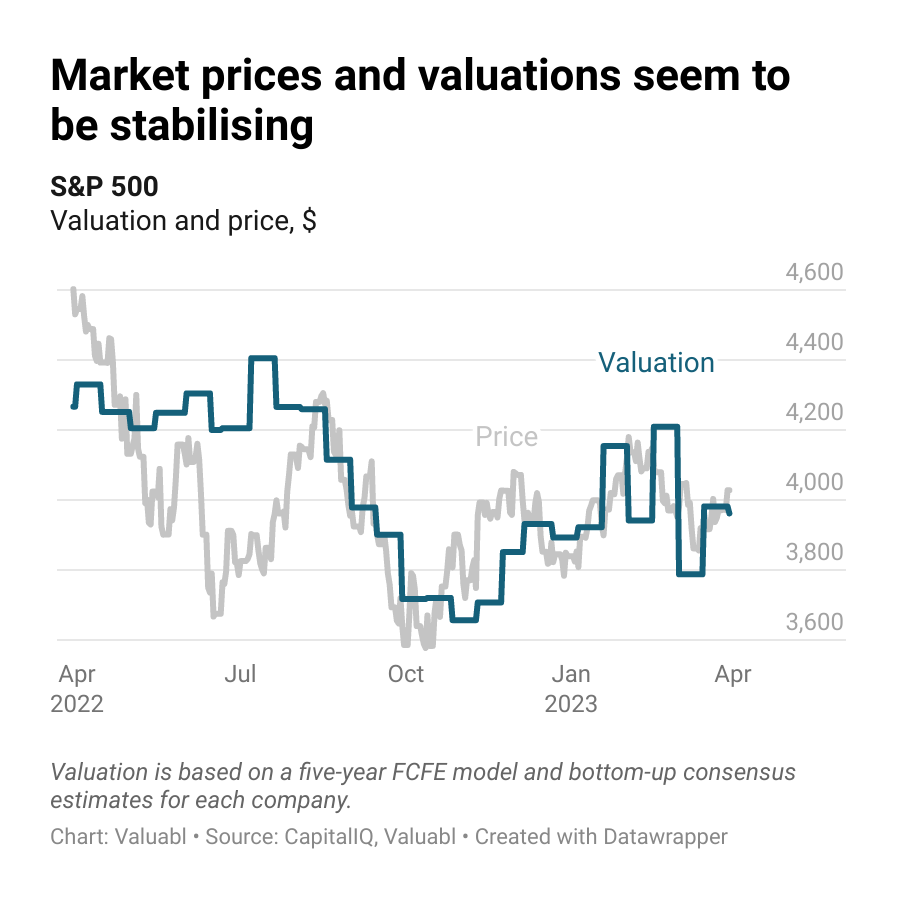

Stock prices rose last fortnight. The S&P 500, an index of big American companies, climbed 3% to 4,028. The market is up from its October lows but is 13% below where it was last year.

I value the S&P 500 at 3,962, which suggests it is fair value. My valuation has thrashed back and forth in recent months. Significant movements in bond yields and consensus estimates are to blame. Traders and analysts were uncertain about the future, which showed up in estimates. But markets have calmed down, and this week’s valuation hasn’t changed much.

The companies in the index earned $1,628bn in the past year. They paid out $514bn in dividends, bought back $978bn worth of shares, and issued $70bn of equity.

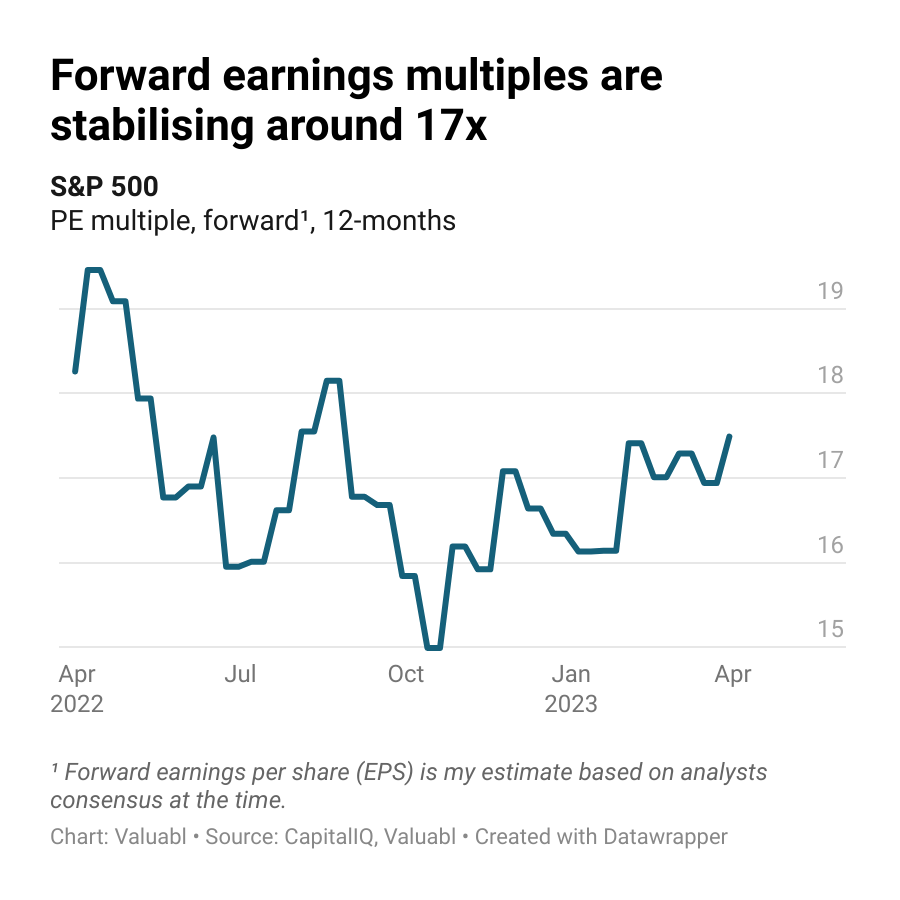

The forward price-earnings (PE) ratio rose to 17.5x. My 12-month forward earnings per share (EPS) estimate for the index also climbed slightly.

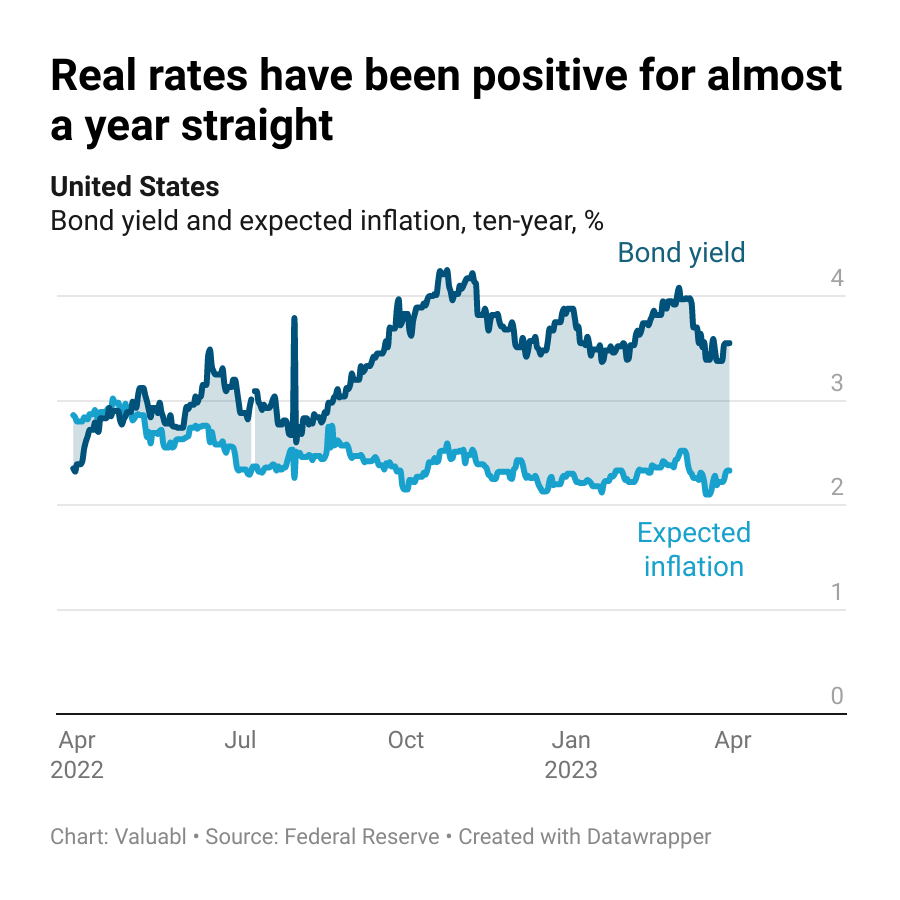

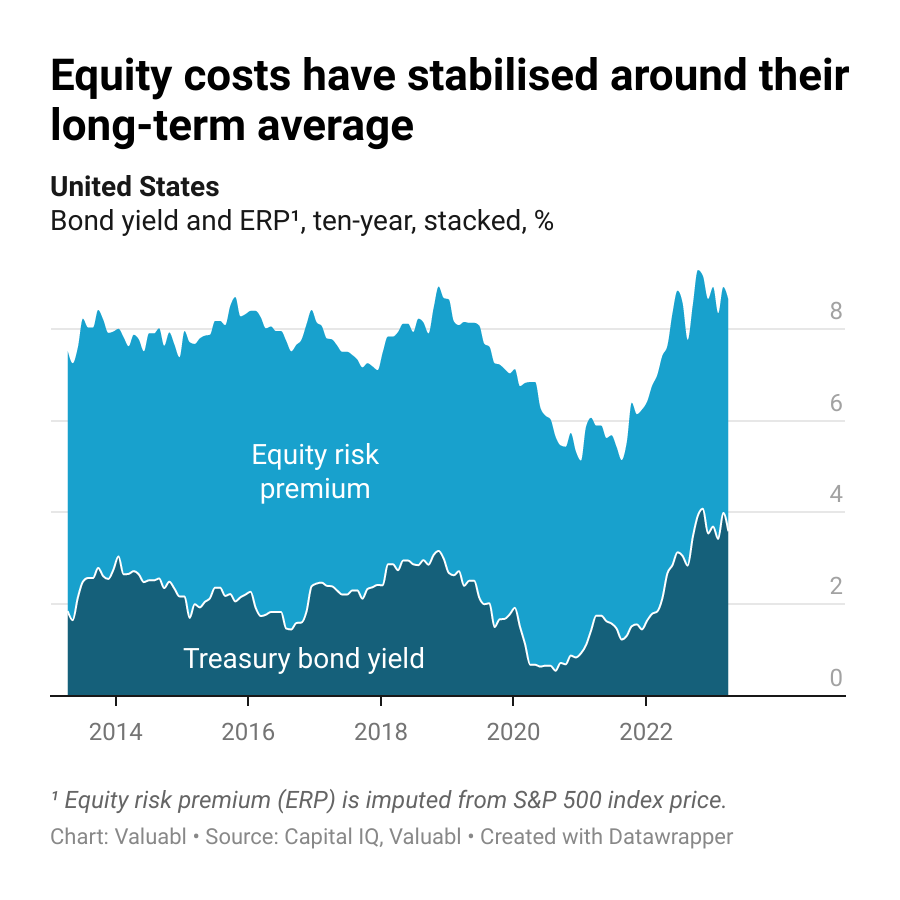

Government bond prices fell as investors calmed down. Yields, which move the opposite way to prices, rose. The ten-year Treasury yield, a critical financial variable, increased 4 basis points (bp) to 3.6%. Investors expect inflation to average 2.3% over the next decade, down 53bp in the past year.

The real interest rate, the gap between yields and expected inflation, didn’t change. Still, these inflation-adjusted rates are up almost two percentage points in the past year.

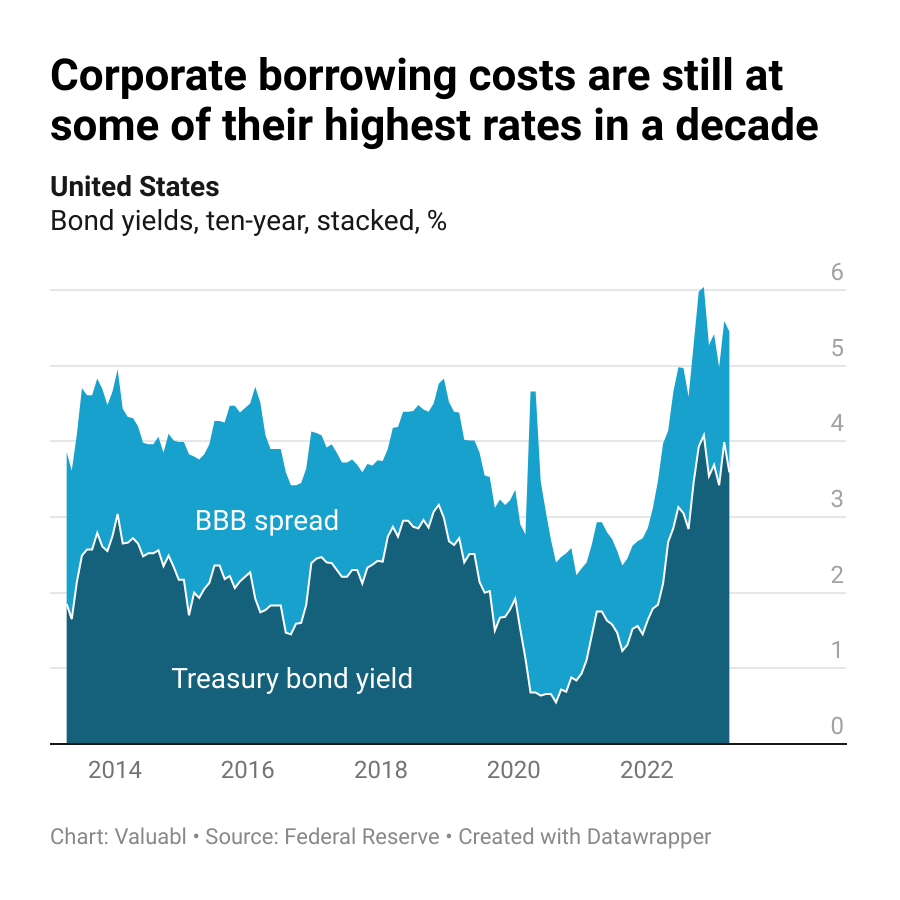

Corporate bond prices rose. Credit spreads, the extra return creditors demand to lend to a company instead of the government, dropped 12bp to 1.8%. While the cost of debt, the annual return lenders expect when lending to these companies, fell 8bp to 5.4%.

Refinancing costs are up 1.4 percentage points in the past year. The ruckus caused by SVB and Signature banks’ collapse, which had pushed up the price of risk, seems to be subsiding.

The equity risk premium (ERP), the extra return investors want to buy stocks instead of bonds, dropped 20bp to 5%. It’s now 24bp below where it was last year. The cost of equity, the total annual return these investors expect, fell 16bp to 8.6%. These expected returns are in line with their long-term average.