Vol. 3, No. 11 — Waiting for Godot

Holding cash while waiting for a fat pitch is overrated; America is unlikely to have a recession this year; Stock valuations have started to look frothy; Value in groceries

Welcome to Valuabl, a twice-monthly newsletter providing financial analysis with a value-oriented perspective. Here to help bankers and fund managers make smarter investment decisions. Learn more

In this issue

Quotation from Warren E. Buffett

Job board

Cartoon: Striking out

Waiting for Godot

Cost of capital

Monetary mechanics

Global stocktake

Rank and file

Debt cycle monitor

Investment idea

Read time: 31 minutes

Quotation

“Investing is the greatest business in the world because you never have to swing… There's no penalty except opportunity. All day you wait for the pitch you like; then, when the fielders are asleep, you step up and hit it.”

— Warren E. Buffett

Job board

Looking for high-quality people? Thousands of bankers, analysts, and investors read Valuabl every fortnight. Email valuabl@substack.com to post your role here for free.

Cartoon: Striking out

Waiting for Godot

Holding cash while waiting for a fat pitch is overrated

•••

Forty thousand people descend each year on a convention centre in middle America. They're there to learn from Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger, two of finance's best minds. But the hero worship runs deep. Slapping a value investor's mother is safer than critiquing their idol. And few of Buffett's commandments get more head nods than to 'wait for a fat pitch', a baseball analogy that means an easy-to-hit ball. Buffett uses this phrase to suggest you hold cash until you find an excellent investment. The idea is intuitive and sounds sensible. But for most of us, waiting for Godot will make us poorer than we would otherwise be.

First, the opportunity cost of doing nothing is enormous. American stocks have returned 9.6% per year on average over the past century. If you had a hundred bucks and waited a year, on average, you would have had to buy something worth $110 for that same $100. In five years, it would be $158, or a 37% discount. While ten years of thumb-twiddling would have put the needed discount closer to 60%. A tall ask.

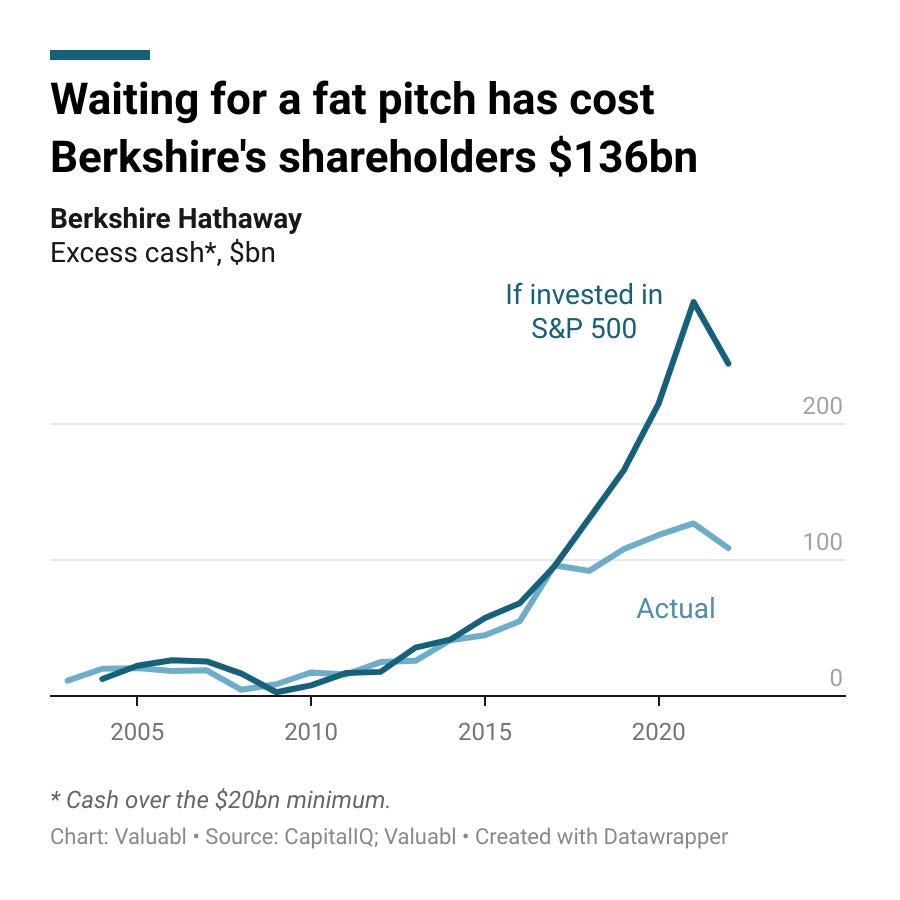

Mr Buffett, for example, has cost Berkshire's investors $136bn by waiting to invest or distribute excess cash over the last two decades. A simple policy of putting the spare money above $20bn into the S&P 500 would have left investors far better off. That's not to say Buffett won't make some incredible buys. Instead, he must buy assets worth $244bn with his $109bn of cash to make up for the loss.

The longer an investor waits, the bigger the future discount must be. Time marches on without mercy. Uninvested money burns a hole in the investor's pocket, increasing the return demanded. This lowers the chance of finding an investment that will make the opportunity cost back. More stocks trade at a 5% discount to intrinsic value than ones at 50%. And even fewer still that will move the needle on a hundred billion.

Second, timing the market is almost impossible. JPMorgan, a bank, found that if punters put everything in the index from 1999 to 2018, they made 6% per year. But, if they missed the ten best days, that dropped to 2%. Staying in ensured they got the upticks, which were the bulk of returns.

When investors try to buy the dip instead, their returns don't improve. Since 1928, the S&P 500 has had 26 down years. Five saw a quarter of the value knocked off in a calendar year. If you bought each time the market dropped 25%, you would have made 9% per year over the following decade. That's no better than the average market return.

Moreover, biases wreak havoc on our ability to time the market. Traders tend to panic sell during downturns and become overconfident during the boom. They buy high and sell low—the opposite of what they should do. The same study showed that investors got lower returns than the stocks they invested in. Their timing sucks. By waiting, investors miss out on the big upswings and do worse than the market if they try to time their buys instead.

Thumb-twiddlers argue that cash has option value. That is true if you can access deals you wouldn't otherwise be able to, most likely during a financial panic. Further, you would need the ability to value and time those purchases well. And, the payoff must be greater than the opportunity cost of waiting. But the evidence that average investors can do this is slim to none. Mr Buffett, on the other hand, has an incredible track record and cash in his hands had immense option value in the past. But it gets harder and harder with size.

For the vast majority of investors, cash will have no option value. In fact, holding onto it is a negative. As Pozzo, the pompous slave owner in Samuel Beckett's play Waiting for Godot, says, "that's how it is on this bitch of an earth."

Cost of capital

Finance’s most important yet misunderstood price is capital. Here’s what happened to the cost of money in the past fortnight.

•••

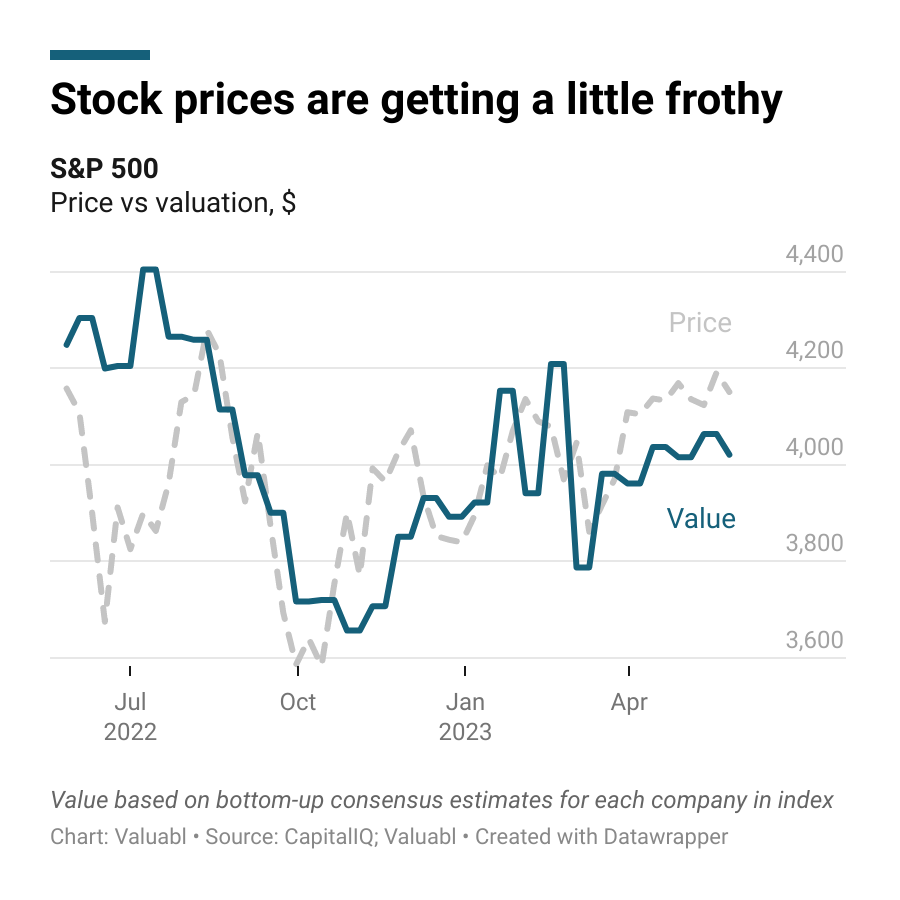

Stock prices rose last fortnight. The S&P 500, an index of big American companies, climbed 1% to 4,151. The market is now 4% higher a year ago. Stock prices have been resilient in the face of rate hikes. The central bank has hiked interest rates from 1% to 5% in that time.

I value the index at 4,021, which suggests it is slightly overvalued. Excitement over the future of artificial intelligence has buoyed prices for tech companies. NVIDIA, a chip-maker, in particular, has done well lately. But it looks like the market is getting a little frothy.

The companies in the index earned $1,642bn in the past year. They paid out $523bn in dividends, bought back $926bn worth of shares, and issued $68bn of equity.

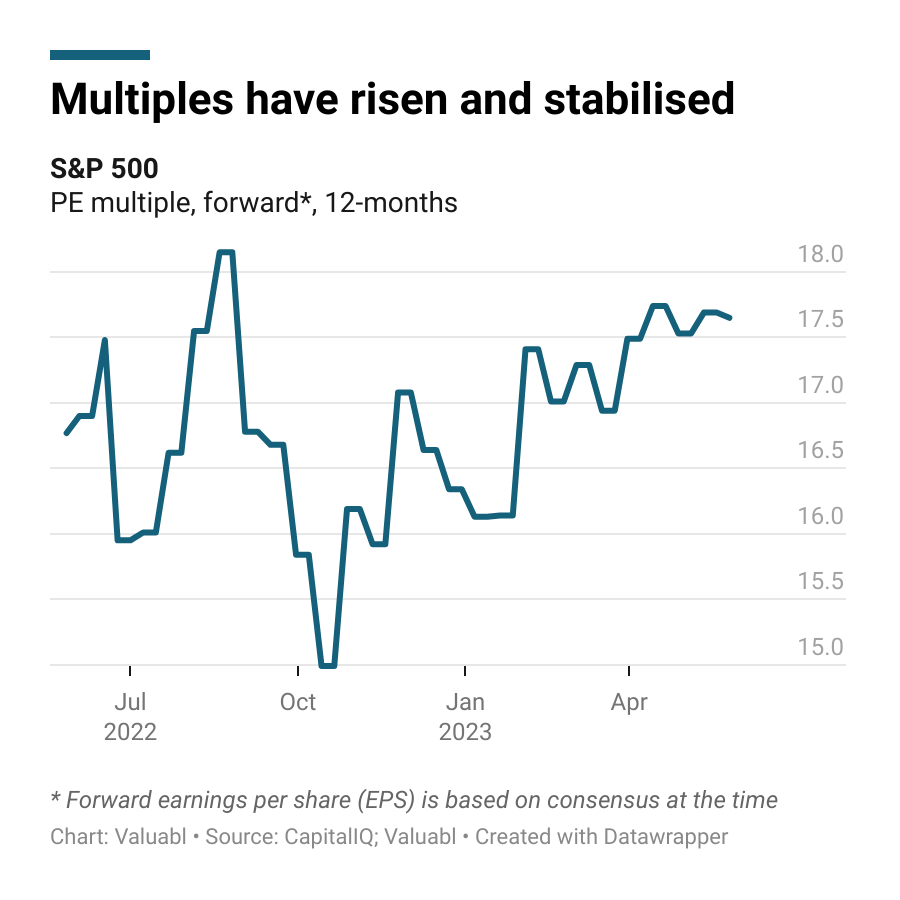

The forward price-earnings (PE) ratio stayed at 17.7x. My 12-month forward earnings per share (EPS) estimate for the index also climbed from $233.40 per share to $235.20.

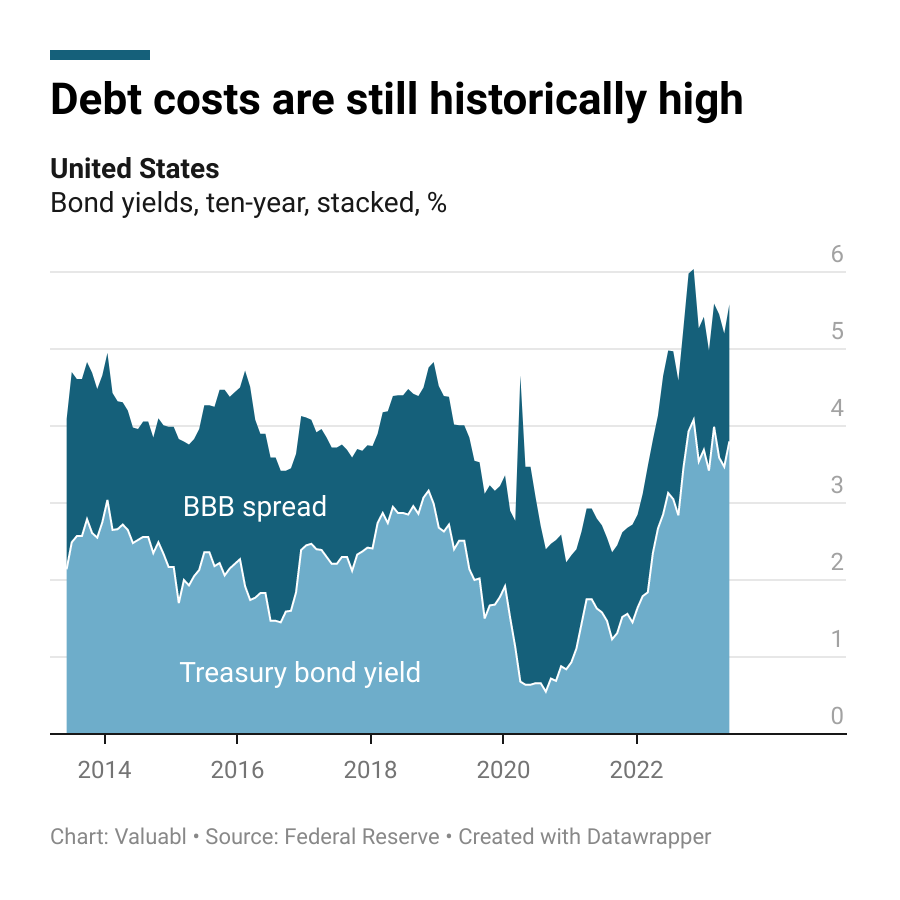

Government bond prices fell. The ten-year Treasury yield, which moves the opposite way to prices, jumped 34 basis points (bp) to 3.7%. Investors expect inflation to average 2.2% over the next decade. Their inflation forecast has fallen 31bp in the past year.

The real interest rate, the gap between yields and expected inflation, rose 25bp to 1.5%. These inflation-adjusted rates have been positive for over whole year.

Corporate bond prices also fell. Credit spreads, the extra return creditors demand to lend to a company instead of the government, dropped 5bp to 1.8%. While the cost of debt, the annual return lenders expect when lending to these companies, rose 29bp to 5.5%.

Government bond yields are still the driving force behind changes in the cost of capital.

The equity risk premium (ERP), the extra return investors want to buy stocks instead of bonds, fell 8bp to 5%. It’s now 52bp below where it was last year. The cost of equity, the total annual return these investors expect, rose 26bp to 8.7%. These expected returns are in line with their long-term average, and have stabilised.

Equity investors do not see a recession on the horizon.

Monetary mechanics

The economic forecast calls for thunderstorms. But there are few financial clouds on America’s horizon.

•••

The financial world has braced for a slowdown. The Fed has raised rates at breakneck speed and has stopped bond purchases. If a recession hits America, pundits reckon profits will tank, and stocks will fall by a third. But if they're wrong, markets will continue their rise, and the nay-sayers will have missed out. Is the economy more potent than most expect? Yes, and a recession this year is unlikely.

First, rate hikes have stimulated, not snuffed, the economy. They have increased the government's interest bill and deficit. That means more money going into the private sector. Over the past year, the nation's interest payments have risen by a third to $1.2trn, an increase of 1% of GDP. Interest payments on government debt are now 4.5% of the nation's income. Unless it finances it with taxes, the deficit, the gap between government spending and taxes, goes up. That creates new money. With the deficit at 5% of national income already and set to increase, that's a lot of cash in the private sector's hands.

While we're still a ways off the interest bill hitting 6% of GDP, as it did in the '80s, higher rates mean increased refinancing costs. Once lawmakers raise the debt ceiling, the Treasury will issue new debt and refinance the old stuff at higher rates. That will increase the interest bill and stimulate demand more.

Second, the country’s net worth has risen despite higher rates, and the job market is robust. According to the Federal Reserve’s Flow of Funds report, the private sector is worth 6% more than a year ago. That is despite a slight drop in households’ net worth. Businesses have prospered while families are a little poorer in inflation-adjusted terms. The relative strength of corporate balance sheets helped. Higher interest rates pushed money into the economy and companies expanded.

Also, there are almost two job openings for every person looking for one—one of the highest rates on record. As households are poorer, but firms are richer, wages haven't had to rise despite the job market's imbalance. Companies feel rich, so aren’t under pressure to fill positions. Workers feel poorer, so are under pressure to work more. Unless business conditions worsen, unemployment will remain low, and the country’s net worth will continue to grow.

Third, bank lending is still strong, which supports spending. Businesses and landlords have continued to borrow at normal levels despite higher rates and bank failures. Landlords borrowed another 2% of GDP from banks in the past year and businesses another 1%. Banks have, in total, lent out another 5% of GDP in the past year. More interest income and higher net worths have kept credit demand alive. With banks continuing to lend and the private sector wanting those loans, spending and investment will continue to rise. When combined with the deficit, bank loans have helped the private sector's spending power grow by about 10% of GDP.

But traders think a recession is imminent. Long-term bond yields are lower than short-term ones—an inverted yield curve—and futures’ prices suggest rate cuts from November. Usually, these suggest bond and interest rate traders reckon a recession is coming. And they’ve been good forecasters in the past. But the market is wrong this time as it overestimates the tightening effect of the rate hikes. It has missed that at high public debt levels, rate hikes add to the deficit and stimulate the economy. That makes a recession and early rate cuts this year much less likely than usual.

Now is not the winter of our discontent.