Vol. 3, No. 17 — We don't Work

WeWork is on the brink of collapse; Good companies don’t always make attractive investments; The market has started to correct; The French face a deleveraging; Value in chocolate and coffee pods

In this issue

Quote from Adam Neumann

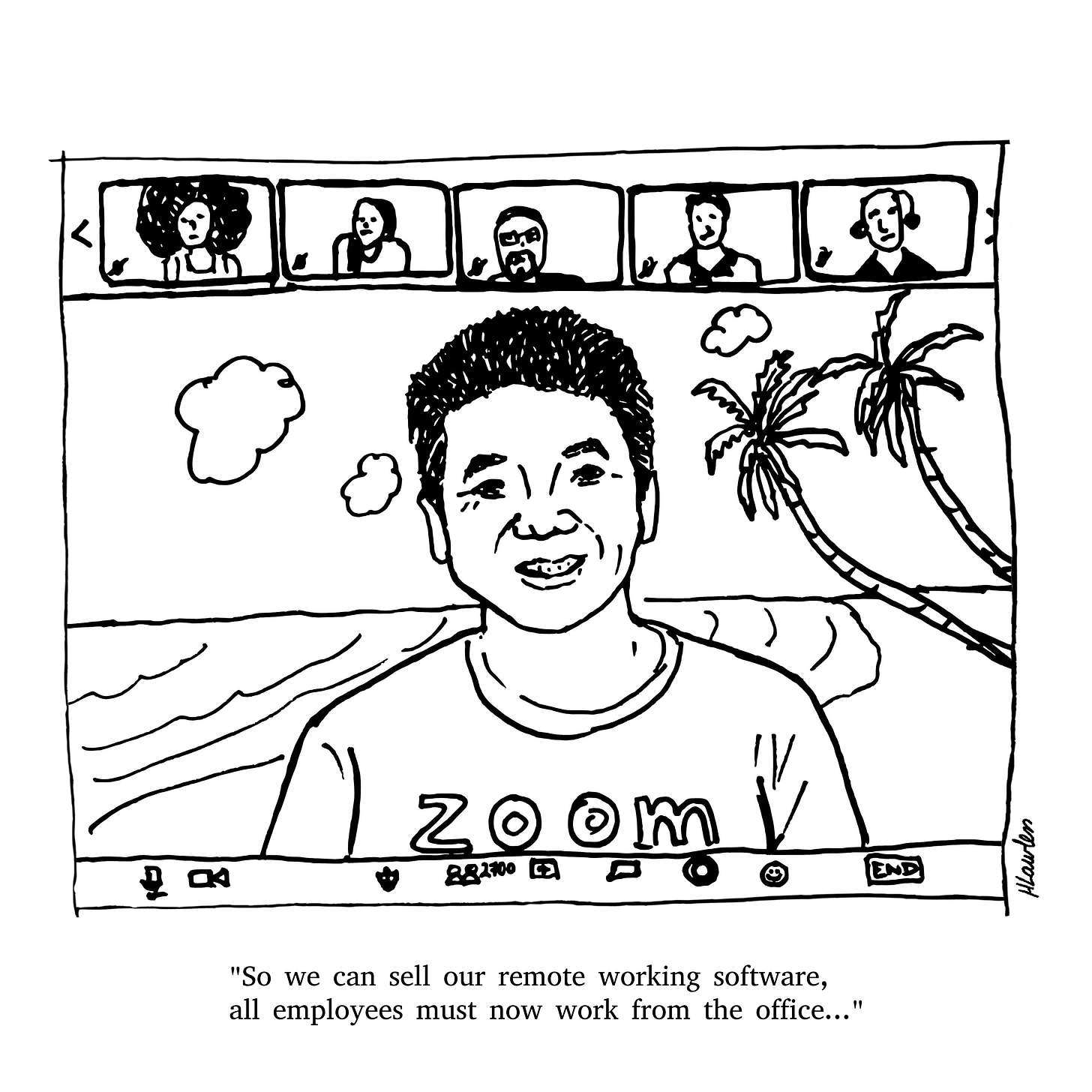

Cartoon: Never get high on your own supply

We don’t Work

The quality mirage

Cost of capital

Regions and sectors

Stock screen

Debt cycle monitor

Investment idea: Nestlé S.A.

Read time: 26 minutes

Quotation

“You never know who you're talking to. Don't limit a young student's dream because that's how we change the world.”

— Adam Neumann

Cartoon: Never get high on your own supply

We don’t Work

WeWork, the trendy flexible office space provider, is on the brink of collapse. Here’s why

•••

Adam Neumann, WeWork’s big-thinking and heavy-drinking founder, once said he wanted to be the king of the world. He also said he wanted to be a trillionaire and to live forever. No one could accuse him of dreaming small. But the company he founded and got rich and famous for is on the verge of collapse. WeWork is failing for three reasons: the business model is broken, office space demand is crashing, and investors have ignored the leverage effect of leases.

First, the WeWork business model doesn’t work. Over the last ten years, the firm has produced average operating margins of -89%. They had improved slightly during the previous two years but were still -26% last quarter. That puts WeWork’s margins in the bottom 5% of all global real estate management firms. With fat operating losses, the company burns through a lot of cash. In fact, they’ve lost a cumulative $13bn in the past decade on $16bn of revenue.

Moreover, the business is capital heavy and reliant on raising outside money. Maintaining and managing real estate costs a small fortune, and revenues are sparse. WeWork’s sales-to-invested capital ratio is 0.2x, bang on the industry’s median. That means it has had to invest $5 for every one that hits the top line. That makes expansion expensive.

Heavy losses and rapid growth meant the firm needed to continue to attract investors. According to Crunchbase, a company tracker, WeWork raised $21bn across 22 rounds. But investors now have little to show for it. The company has burned that money. As expansion is so costly, as soon as funding slows, so does growth.

Since this business has enormous fixed costs, the company had to get massive to become profitable. That would have brought those fixed costs down proportionally, widening margins. It was happening, but they needed a much longer runway to get there. Since it took so much capital to grow, and they were losing money, investors would always eventually turn off the taps. And the business would fail.

Second, office space demand is in free fall. Knight Frank, a British real estate agency, says companies in London are ditching a quarter of their office space. Across the pond, Rising Realty Partners, a New York property manager, reckons there’s enough empty office space there to fill 26 Empire State Buildings. Flexible and remote working is to blame. As a result, WeWork’s top line, which was taking off pre-pandemic, has flatlined. Back then, sales doubled yearly, but now they barely grow faster than inflation. People don’t need to commute and sit at a desk all day any more. That has meant businesses don’t need as much space to function, hitting cubicle providers like WeWork right as they need the opposite.

Finally, investors failed to recognise that operating leases are debt. They completely mispriced the risks. Assuming WeWork would achieve profit margins in the industry’s top quartile, if you don’t treat leases as debt, the shares are worth about $1.80. That’s where they were at the start of the year. But if you treat the leases as debt, that reduces the equity value to zero. If investors had done this right, they would have recognised it years ago.

Real estate is a high-leverage industry, but WeWork is on another planet. The median public real estate manager’s debt is half the capital invested. For WeWork, it’s 127%. That means they have more leverage than 99% of all firms in the industry. But the catch is that’s only if you include leases. If you ignore them, the picture is a much rosier 21% debt-to-capital, a smidge below the industry median of 25%. That’s what investors must have done.

There’s a lesson in this: treat leases like debt, as they should be, and you’ll make smarter investment decisions. If WeWork’s investors had done this, they would have lost less money and pushed for restructuring earlier. This bankruptcy might be the time.

The quality mirage

Good companies don’t always make attractive investments. It depends on the price.

•••

Warren Buffett reckons, "It's better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price". Not only is this misleading advice, but it's also counter to what he did. When Buffett was young, he bought cheap crappy companies and made 32% a year—delicious returns. But it's difficult for him to move the needle now that he manages billions. So, he's changed his tune, and his disciples chant the above psalm. To the quality-crazed, it's usually a cop-out for lazy valuation work. But investors should dig deeper, as good companies aren't always suitable investments. Instead, returns depend on the price paid relative to the intrinsic value.