Vol. 3, No. 23 — Mortgage: Impossible

Homeownership is out of reach for the average American family; The implied return on stocks is at a multi-decade high; Real estate losses and outflows continue; Value in milk and infant formula

In this issue

Cartoon: WeCommute

Mortgage: Impossible

Cost of capital

Regions and sectors

Stock screen

Debt cycle monitor

Investment idea: The a2 Milk Company

Read time: 41 minutes

Quote

“Never buy a stock because it has had a big decline from its previous high.”

— Jesse Livermore

Cartoon: WeCommute

Mortgage: Impossible

Homeownership is out of reach for the average American family. Unless something changes, houses will only be a plaything for the rich rather than a place to live.

•••

American house prices have defied gravity. Despite one of history's most aggressive interest rate hiking cycles, home prices have marched ever higher. As a result, the white-picket-fence American dream is dead. Homeownership is now out of reach for the average family. There are three reasons for this: First, saving for a deposit takes over a decade. Second, mortgage payments have soared. And third, saving or paying down a mortgage is getting less impactful. Homeownership will remain a pipe dream for many unless something dramatic fixes affordability.

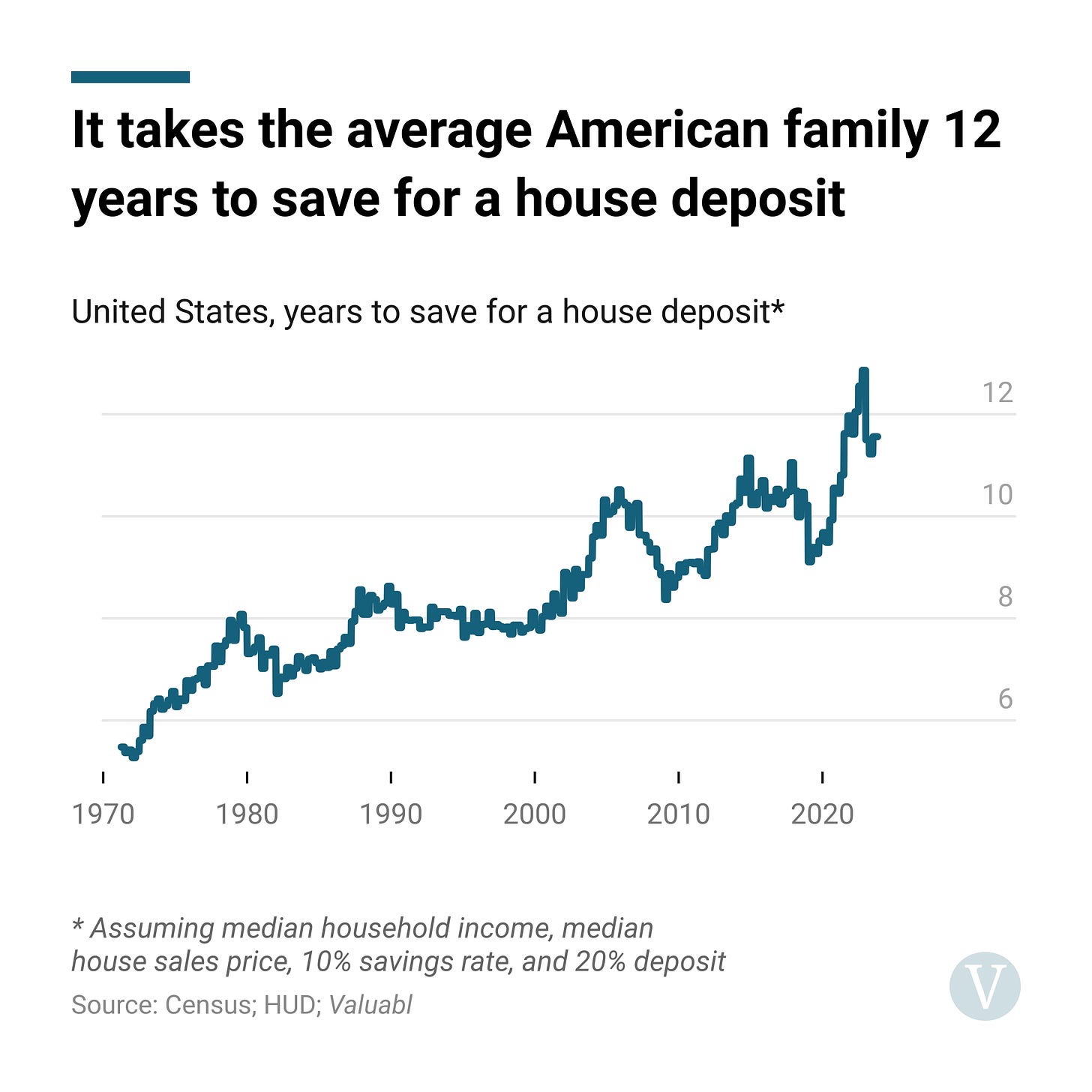

It now takes a helluva long time to save for a house deposit. Using the latest numbers, it would take the average American household 12 years to save for a deposit—a seventh of their life. This calculation assumes a 20% deposit and that families can save 10% of their pre-tax income. It also considers a median household income of $74,580 and a median house price of $431,000.

This metric relies on averages, though. It doesn’t reflect every nook and cranny of the market. First-time homebuyers, for example, usually have lower incomes as they're earlier in their careers. But they'll also buy smaller, cheaper houses, not the average house. Still, 12 years is a long time, and it's illustrative of the underlying problem.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, American workers hit their peak earnings of about $113,000 a year between 45 and 54 years old. That's far above the $62,000 average for workers under 35—which is also below the median. For savers starting work after university at 22, it would take closer to 16 years to save for the deposit on the average home.

But, to counteract that, first-time shoppers will search at the cheaper end of town. As a result, the two will balance out, meaning first-time home buyers would be about 34 years old. That marries up with the data. According to the National Association of Realtors, in 2022, first home buyers were 36 years old on average, up from 33 the year before. Buying your first house is now a lot of work and a long time spent saving.

As prices continue to rise, deposit gathering will take longer and longer. Young people with wealthy families will soon be the only ones able to get a deposit. That will widen inequality and entrench housing as a luxury good. The average time to save a deposit is now double what it was in the '70s. Back then, it took five years if you put away 10% of your pre-tax income. Now it's 12. That means average first-time buyers could have been anywhere from 23 to 27. Pushing home ownership back by seven years has already affected birth rates and wealth. As it takes longer to get a house, people have delayed when they have children and trimmed how many they have. Birth rates are plummeting. But, if wealthy families can pony up deposits for their children in their 20s, that sets them up for breeding and wealth earlier.

Mortgages are as unaffordable as they were in the 1980s. For those who had saved up a deposit, most of their income will now go straight to the bank. But, unlike back then, paying down the debt is now arduous and pointless. As mortgage rates have risen so much over the past two years, the annual interest payment on a new 30-year fixed rate mortgage with 20% down is now $27,000. That's almost triple the $8,000 it cost two years ago. That interest bill is now a weighty 36% of pre-tax household income, the highest level of unaffordability since the '80s.

But the price-to-income ratio was much lower then, so mortgages were smaller. That meant families could pay off the mortgage faster than they could now. Payments reduced the burden much faster back then. During the '80s, if home-owning families put 10% of their pre-tax income towards trimming the mortgage, they would be debt-free in 16 years. Dedicating 20% would knock that down to eight years. But those home economics no longer work. It would take 38 years for families to pay off the mortgage today. Bumping the savings rate to 20% of income would trim that to a still lengthy 19 years.

Furthermore, in the ‘80s, the interest bill would drop a fair bit as the size of the mortgage did. Putting a tenth of your income into the mortgage back then would reduce your annual interest bill, as a percentage of income, by almost twice what it would do now. That increases the time it takes to pay the mortgage off these days, making the current affordability crisis more painful. Even with prudent saving and pre-payment, there is no relief in sight for modern homebuyers.

It's also getting harder to save. Savings rates have declined, and real incomes, especially for young workers, are stagnant. The personal savings rate, the amount of post-tax income households save, has been in a downtrend since 1970. The rate exploded during the pandemic but has returned to its long-term downtrend. Through the '80s, families kept an average of 10% of their post-tax income. In the 2010s, that dropped to 6%. While it currently sits at a measly 3%.

Real incomes for workers between 25 and 34 years old have stagnated. After adjusting for inflation, the average income has risen a meagre 8% over the past 20 years. And it fell 2% last year. Cost of living pressures not captured by the consumer price index, including student loans, have left people unable to save like they used to. That's not to mention the disincentivising effect of low rates.

That all makes putting away 10% a year less and less realistic. At a 3% savings rate, it would take over 35 years to get a deposit—phooey to that! Buying a house has become impossible for the average person. Unless something changes, they'll get further out of reach.