Vol. 3, No. 8 — The God delusion: How tech-bros mistook operating leverage for genius

Tech companies and investors have discovered that operating leverage is a double-edged sword; The S&P 500 is fair value; A recession looks increasingly less likely; And value in a telecom giant

Welcome to Valuabl, a twice-monthly periodical that provides an illuminating blend of value-focused investment analysis and data-driven economic commentary. Learn more

In today’s issue

Cartoon: As safe as houses

The God delusion: How tech-bros mistook operating leverage for genius (6 minutes)

Cost of capital (3 minutes)

Global stocktake (3 minutes)

Rank and file (1 minute)

Credit creation, cause and effects (6 minutes)

Debt cycle monitor (1 minute)

Investment idea (17 minutes)

"The four most dangerous words in investing are: 'this time it's different'." — John Templeton

Cartoon: As safe as houses

The God delusion: How tech-bros mistook operating leverage for genius

During the boom, tech-heads spruiked their investment records while belittling traditional jobs. But the tides have turned. Instead of soaking in the schadenfreude, we should learn from their mistakes.

•••

It's been a rough couple of years for software companies. Tech stocks, which were propelled ever higher by low-interest rates and investor imagination, have been falling. Many employees at these firms have lost their jobs. According to TrueUp, a tech company tracker, the firms they watch have fired 447,000 workers in the past year—that's more than 1,200 sackings a day. Many laid off workers can't find a new job as the number of software development job listings has dwindled.

But why has the market and economy punished these previous high-fliers so? The operating leverage in their business models, and their stakeholders' ignorance of its downside, are to blame. Those companies did well when interest rates were low, and the economy boomed. Investors praised their high-fixed, low-variable cost structures. Bosses ignored the pitfalls of leverage and hired like mad, not expecting the good times to end. But on the way down, workers and bosses have discovered that operating leverage is a double-edged sword. And they're being punished for their previous hubris.

What is operating leverage?

When a significant proportion of a company's costs don't change, they're said to have a lot of operating leverage. This form of leverage is the extent to which a business's fixed costs—the expenses that don’t change whether you sell 1,000 or 1m units—impact its profits. When many of the firm's expenses are fixed, profit margins expand when sales do. That is because the fixed costs get spread out over a larger output. But if sales drop, the opposite happens, and profits tank.

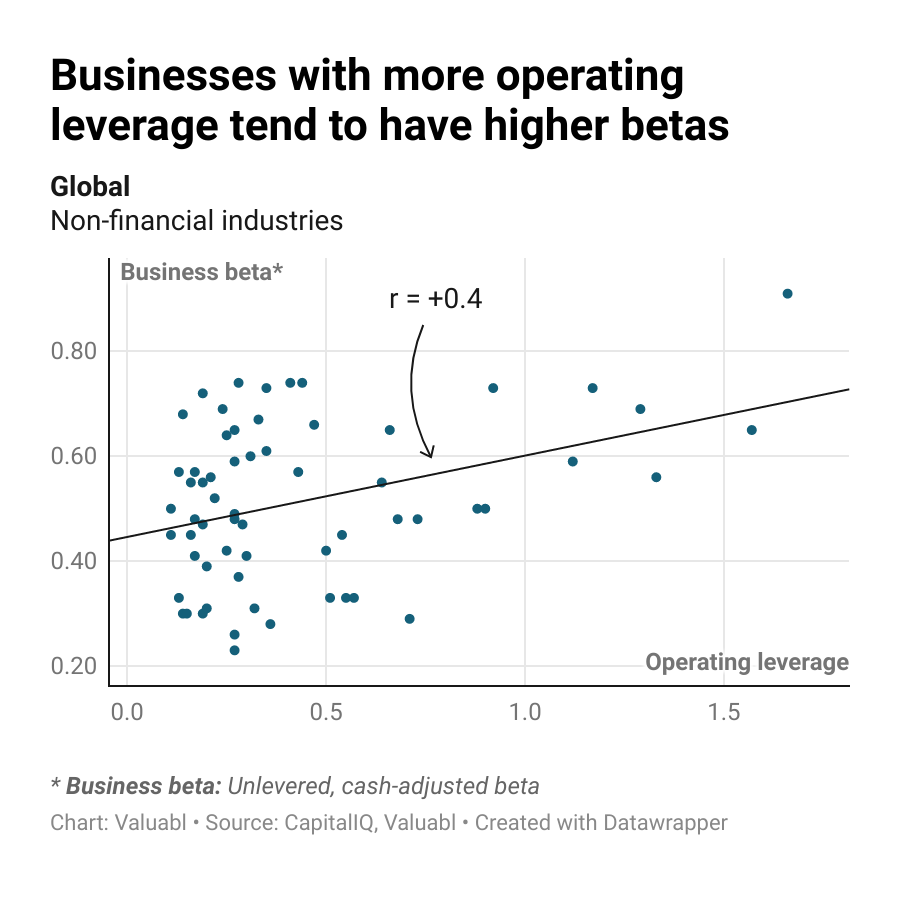

High operating leverage can increase profits and help create new jobs when things are going well. But it makes a company more vulnerable to losses when things go wrong. Like debt, it makes cash flows more volatile. As a result, on average, an industry with a higher fixed-to-variable cost ratio will have a higher beta, a measure of relative riskiness.

Just like financial leverage, operational leverage makes a business model riskier and should push up its cost of capital. But many investors ignored this during the boom. They expected these companies to generate fat profits thanks to the operating leverage in their business models. But they failed to discount the extra risk. They saw the rising profits and valuations and thought it was thanks to their own genius.

Oh, how the mighty have fallen—God complexes and crocodile tears

As rates fell and tech stocks boomed, some of those in the tech world developed god complexes. In an interview, Chamath Palihapitiya, a prominent tech-apostle, said, "I'm not a genius, but I'm pretty close." But, when the Fed raised rates in an effort to slow inflation and the economy, it all came undone. “While 2022 was a challenge,” Chamath wrote in his latest annual letter, “the valor and lessons learned came from actually being in the arena, not commenting from the sidelines.”

The tech stock selloff was partly driven by interest rates pushing up capital costs but also by lower growth expectations. Investors reckoned tech firms' large fixed-cost bases would crush profitability as economic growth slowed. Consequently, the NASDAQ 100, a tech-focused index, tanked. In fact, despite bouncing back in recent months, it is still 21% below its December 2021 high.

IT companies have some of the highest operating leverage ratios of all businesses. In fact, of the 70 non-financial industry classifications in my data sample, the four with the highest operating leverage ratios are tech related. When growth started to drop, bosses, knowing that the slowdown would crush their profits, sacked workers and slammed the brakes on hiring. Hubris turned to humility, and some bosses have penned grovelling apologies to their investors and former staff. One CEO even took to LinkedIn to post a crying selfie.

Schadenfreude—a German word that means to take pleasure in others’ misfortune—would be easy. But it would be a mistake. Instead, we should learn from their hubris and remember that most things are outside our control. Investors and bosses should remember that operational leverage functions like financial leverage, magnifying the economic cycle. On the way up, it will produce sweet-tasting profits and job gains. But on the way down, it will sting. If we forget this lesson, we will see even more god complexes and crocodile tears next time.

“They mistook leverage for genius” — Steve Eisman, on the 2008 crisis

Cost of capital

Finance’s most important yet misunderstood price is capital. Here’s what happened to the cost of money in the past fortnight.

•••

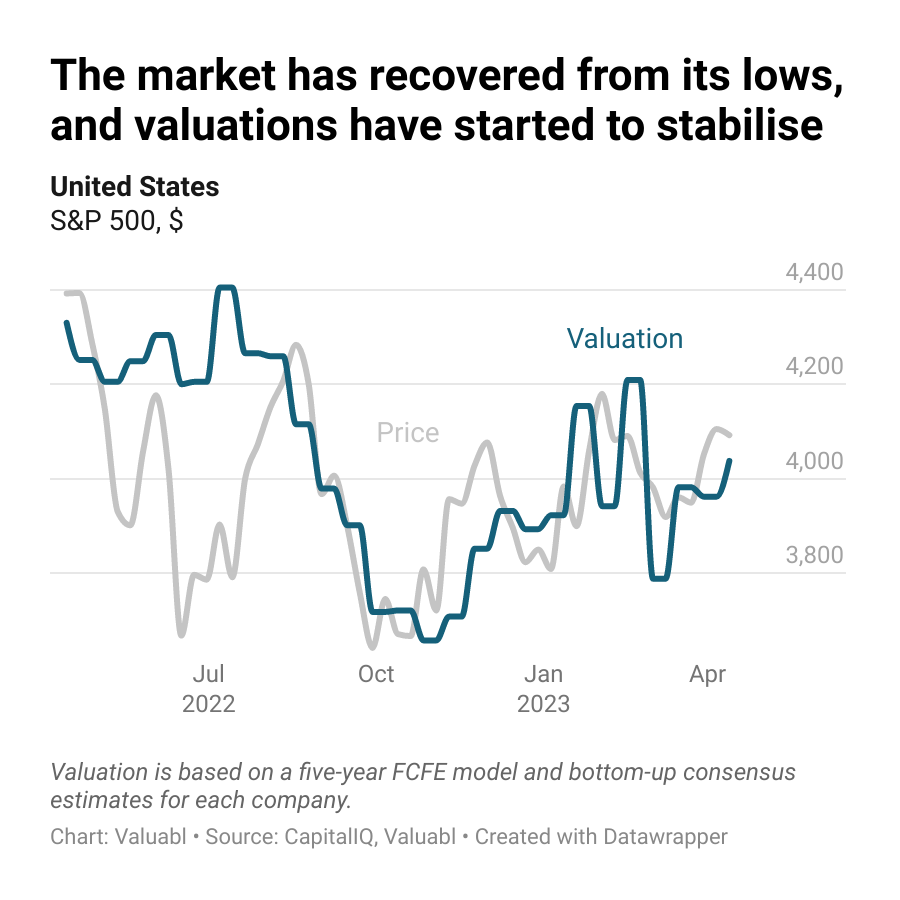

Stock prices rose last fortnight. The S&P 500, an index of big American companies, climbed 2% to 4,092. The market is up from its October lows but still 7% below where it was last year.

I value the index at 4,037, which suggests it is fair value. My valuation has thrashed back and forth in recent months. Significant movements in bond yields and consensus estimates are to blame. Traders and analysts were uncertain about the future, which showed up in estimates. But markets have calmed down, and the past few valuations have hardly changed.

The companies in the index earned $1,623bn in the past year. They paid out $517bn in dividends, bought back $983bn worth of shares, and issued $72bn of equity.

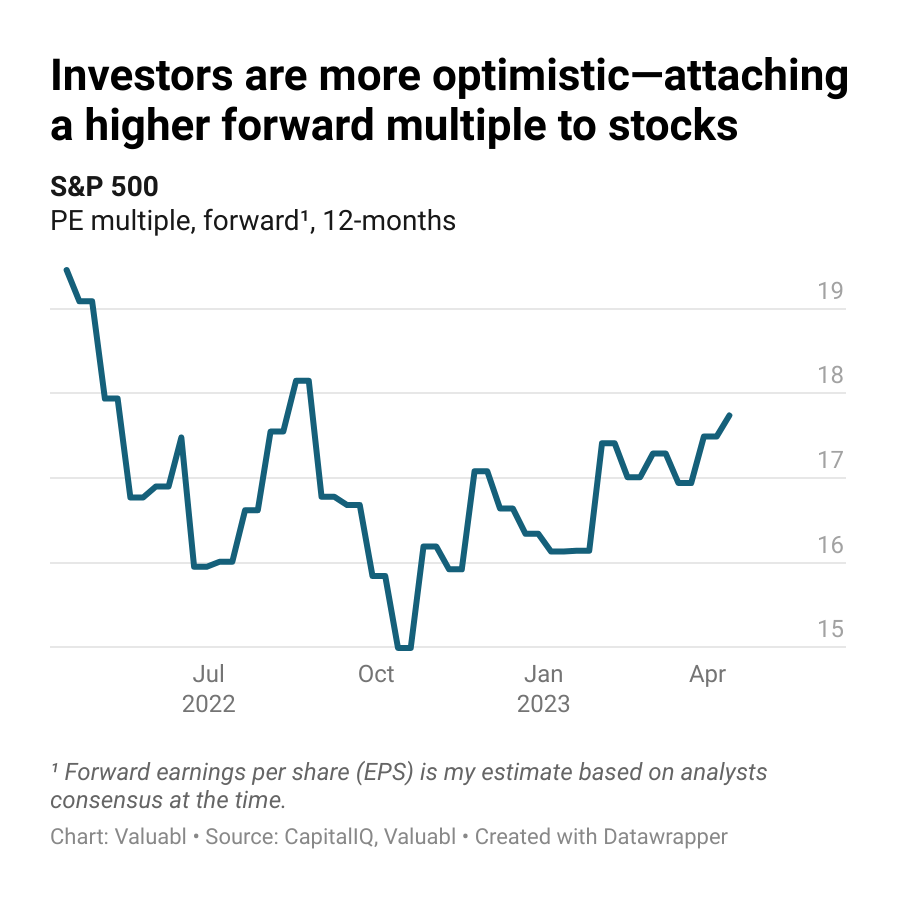

The forward price-earnings (PE) ratio rose to 17.7x. My 12-month forward earnings per share (EPS) estimate for the index also climbed slightly from $230.20 per share to $230.60.

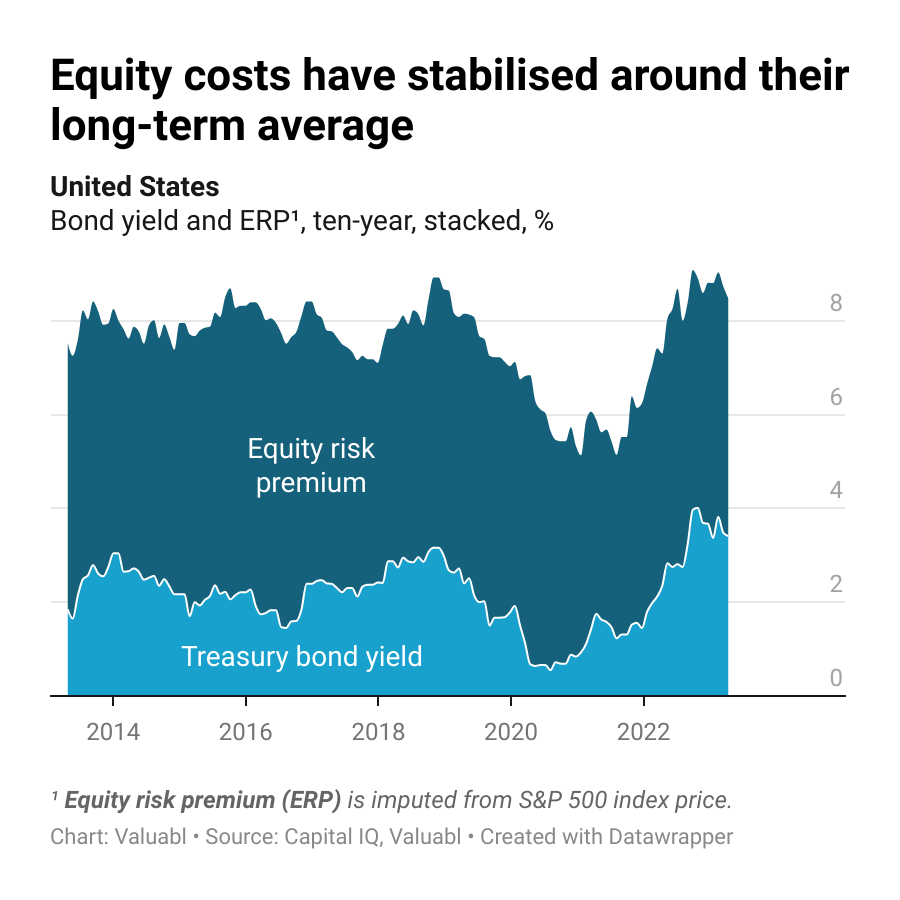

Government bond prices rose. Yields, which move the opposite way to prices, dropped. The ten-year Treasury yield, a critical financial variable, fell 14 basis points (bp) to 3.4%. Investors expect inflation to average 2.3% over the next decade. Their inflation forecast has fallen 59bp in the past year.

The real interest rate, the gap between yields and expected inflation, fell 8bp to 1.2%. Still, these inflation-adjusted rates have been positive for almost a whole year—they’re 130bp higher than where they were.

Corporate bond prices rose. Credit spreads, the extra return creditors demand to lend to a company instead of the government, dropped 7bp to 1.8%. While the cost of debt, the annual return lenders expect when lending to these companies, fell 21bp to 5.2%.

Refinancing costs are up one percentage point in the past year. The ruckus caused by SVB and Signature banks’ collapse, which had pushed up the price of risk, seems to be subsiding.

The equity risk premium (ERP), the extra return investors want to buy stocks instead of bonds, rose 1bp to 5.1%. It’s now 11bp below where it was last year. The cost of equity, the total annual return these investors expect, fell 13bp to 8.5%. These expected returns are in line with their long-term average.