Vol. 4, No. 20 — Gains are wonky

A few stocks drive the majority of returns; Britain's Labour Party are acting like Tories in disguise; The Fed's rate cut won't do much to the economy; A market researcher with 67% upside

Contents

The world this fortnight | A summary of economic and financial news

Finance | Gains are wonky

Letters to the editor | On housing, recessions, and Alibaba shares

Opinion | Tories in disguise

Economics | Smooth sailing

Cost of capital | Analysis of the ever-changing price of money

Investment idea | A market researcher with 67% upside

Indicators | Economic data, markets and commodities

The world this fortnight

Mira Murati, who led the development of ChatGPT, quit as technology boss of OpenAI, an artificial intelligence (AI) developer. The firm is preparing to change its non-profit status to become a public-benefit corporation. This shift would allow OpenAI to pursue turning a profit.

Microsoft signed a deal to reopen Unit 1 of the Three Mile Island nuclear facility to supply carbon-free electricity for 20 years. Managers closed the unit five years ago for financial reasons. It sits next to Unit 2, which closed after a 1979 meltdown, America’s worst nuclear accident.

America’s Justice Department filed an antitrust complaint against Visa, a global payments company. It accused the company of using its dominant position in debit-payment networks to block competition. Visa dismissed the lawsuit as meritless.

Qualcomm approached Intel about a potential friendly takeover. Intel, a chipmaker, has struggled to compete with rivals like Nvidia and AMD in the AI processor market. Following a poor earnings report, Intel lost $32bn in market value and announced a plan to turn its foundry business into an independent subsidiary. Intel’s share price rose after Qualcomm’s offer but is still down 50% this year, leading the company to pause its expansion plans in Germany and Poland.

Pret A Manger, a coffee and snack chain, reported annual global sales of over £1bn ($1.3bn) for the first time. The company operates 690 shops, with 480 in its home country, Britain. Its international growth has fuelled this success. The firm labelled New York the “overseas capital” for customers.

The Federal Reserve cut its primary interest rate for the first time since March 2020. The bank lowered the federal funds rate by half a percentage point to a target range of 4.75% to 5%. The central bank hinted at further cuts this year to address a slowing labour market.

Brazil started to tighten monetary policy by raising interest rates for the first time in two years. The central bank increased its main rate by a quarter percentage point to 10.75% and said more hikes were likely.

China’s central bank introduced several measures to boost stock markets and support the struggling property market. It lowered its policy interest rate by 0.2 percentage points, cut the rate on existing mortgages by 0.5 points, and reduced reserve requirements for banks. Stock markets surged in response.

The Bank of England kept its benchmark interest rate at 5% following a rate cut in August, the first since March 2020. Britain’s annual inflation rate remains steady at 2.2%, though pressures persist in the services sector. Meanwhile, The Bank of Japan held its key interest rate at 0.25%. Ueda Kazuo, the bank’s boss, signalled that they don’t expect to hike again until at least December. ◼︎

HOW TO VALUE STOCKS: This new book will teach you how to value any public company, guiding you step-by-step through the process with real-world examples. Whether you’re new to valuation or an experienced investor, this book will help you make better investment decisions.

Finance | Stock market returns

Gains are wonky

Simple statistics, nothing else, makes it hard to beat the market.

It’s been a solid year for stocks. The S&P 500 index of big American companies is up 21%, as is the Nasdaq 100 index of mostly big tech companies. The MSCI World exchange-traded fund (ETF), which tracks stocks worldwide, has also surged 18%—a hearty return.

Yet most retail and professional investors will be sitting on less eye-popping profits. After all, according to Vanguard, an investment company, fewer than one in ten investors beats the market on average. It probably surprises you that so few people outperform. But it shouldn’t, because stock returns are lopsided.

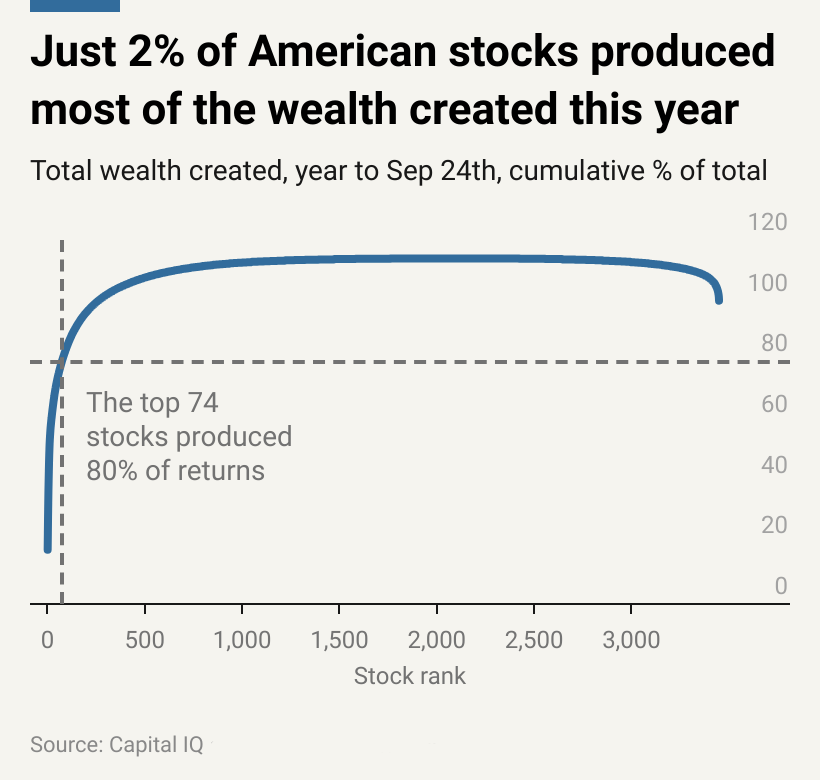

What does it mean to say that stock returns are lopsided? It means that most of the wealth that stock markets produce comes from just a few companies. So far this year, 2% of public American companies produced 80% of returns. Just 74 firms have made $7.8trn of the $9.8trn of new wealth American stocks have created this year.

The results get even more lopsided when considering only the top few firms. Nine companies have produced half of this year’s total return—0.3% of stocks produced 50% of the total return. Furthermore, only one in seven stocks have beaten the average return of all stocks this year.

It’s not just this year, either. This pattern holds over decades of stock returns. Hendrik Bessembinder, an economics professor at Arizona State University, analysed American stock returns from 1926 to 2016. He compared stock returns to what investors would have earned with government bonds—this difference is called excess return. The professor found that just 4% of stocks accounted for 100% of the excess return produced. He also found that just five of the 25,000 stocks in his sample produced 10% of that total wealth. These companies were Apple, ExxonMobil, Microsoft, GE and IBM.

Paradoxically, most stocks also underperform the market. So far this year, only 31% of stocks have beaten the S&P 500, which matches Mr Bessembinder’s findings. The professor found that just one-third of stocks beat the market-weighted-average portfolio. These results all show that the deck is stacked against the aspiring stockpicker. It’s unlikely that investors will build a portfolio that beats the market, much less pick the few companies that produce most of the returns.

Why are stock returns wonky? They’re wonky because of the statistical properties of compounding. To illustrate this, imagine we play a game in which you bet $100 and we flip a coin. If the coin comes up heads, I double your money. If it comes up tails, I take half your money. At the end of the first round, you would have either $200 or $50. Then, we flip again, but you bet your new total. If you had $200 at the end of the first round, you’d have $100 or $400 after the second. If you had $50, then you’d end up with $25 or $100.

Now, imagine there are millions of people playing this game. How many players do you think would have more money than average after five rounds? Intuitively, it feels like about half the players should have more than average, and half should have less. But that’s wrong. Returns are wonky. The correct answer is 20%. A meagre one in five players would have more money than the average. Further, just a quarter of the people would have 80% of the total wealth. And a tenth of them would have half.

The skew we see in stock market returns is because of exponential compounding. A few stocks that do well for a few rounds drag the average up by a lot. Think back to the gambling game. If someone lost for five rounds in a row, they would be down about $97. But if someone wins for five rounds in a row, they would make $3,100—a profit 32x what the loser had lost. That suggests there’s nothing wrong with markets. The lopsidedness we see in stock returns is the result of compounding.

So, what are the implications of this skew? If you’re a good stock picker, you’ll know within a few years, as your picks will do much better than markets. In that case, it doesn’t make sense to diversify. Bet big on your picks and let lopsidedness work for you.

However, if you’re a lousy stock picker, you’ll figure that out quickly as your picks will underperform. In that case, diversify far and wide. Buy an index. Put your money into an ETF of the broader market. That will help you capture some of that lopsidedness for yourself. Stock picking isn’t a game of averages. We should stop thinking of it as such. ◼︎

SPREAD THE LOVE: Share 𝑉𝑎𝑙𝑢𝑎𝑏𝑙 with your friends and colleagues to look like the smartest person they know. You’ll also go into the draw to win a free six-month subscription.

Letters to the editor

Housing

Your article on Argentina’s housing market acts like deregulation is the be-all and end-all, but it completely overlooks the real issue—getting rid of rent controls just leaves everyday people in the lurch (“In a fix”, September 13th) . Sure, lifting controls might mean more properties on the market, but to suggest it’s a magic solution to the housing crisis is nonsense.

Without tenant protections, rents skyrocket, and people who can’t keep up get booted out. Landlords come out on top and renters are left worse off. What’s needed is a more balanced approach, not this slash-and-burn attitude. Deregulation alone isn’t a fix—it’s just making life harder for most people.

— Sophie Evans, London

Kiss my…

You keep saying a recession isn’t coming but I’m going to laugh at you and your losses when it does (“Read my lips”, September 13th). Idiot!

— Anonymous

Alibaba profits

I have a long history with Alibaba and used their platform to find Chinese factories to work with. At some point I also bought their stock, but luckily I panic-sold once it started crashing from $300. I say luckily because the stock just kept declining for four years in a row. More recently, the price became ridiculously low, so I re-opened a position via leveraged Turbos.

When I read your article on the stock, I felt good to know it had your stamp of approval, and I increased my position (“Investment idea”, May 24th). Now I’m massively in the green. In fact, all my Chinese positions are massively up. God bless leveraged Turbos. They’re an amazing tool to use when a beaten stock is unlikely to drop another 50%.

— Amin Eftegarie, Bangkok

Reply directly to this email or send your commentary, critiques, and rebuttals to valuabl@substack.com. You can also direct message ValuablOfficial on X. Please include your name and city. Letters may be edited for brevity.

Opinion | British politics

Tories in disguise

The Labour Party promised to end Tory sleaze and austerity. But they’ve doubled down on both. And it’s a big mistake.

Political sleaze is alive and well. You’d be forgiven for not realising that Britain had a new government. After all, the Labour Party, who are currently in control, are acting and talking like their conservative opponents.

Journalists have outed Keir Starmer, the prime minister, for accepting over £100,000 of freebies during his time as party leader. That’s far more than any other politician. Rachel Reeves, the finance minister, has been dragged into the mud, too. It turns out she accepted free holidays and clothes. It’s disappointing hypocrisy from the party that promised to end Tory sleaze, as they put it, and austerity. Yet, they’ve doubled down on both.

During her speech at the Labour Party conference this year, Ms Reeves droned on about the government not having enough money and needing to make tough choices. Of course, this is nonsense. Lawmakers should dispatch with that dispatch. Instead, they should fund the infrastructure investments the country badly needs and stop worrying about debt.

Unlike a household, the government doesn’t need to balance the books. Households must earn more or borrow if they want to spend more. In contrast, the government creates money when it spends. That means, in stark opposition to what most finance ministers proclaim, Westminster can never run out of pounds. At any stage, the state can buy whatever is for sale. The government simply instructs the Bank of England to enter a larger digit in the seller’s bank account—job done.