Vol. 2, No. 1

Welcome to Valuabl 2022; The cost of capital in January; On global equity risk premiums and EM bond volatility; A deep dive into my best idea of the fortnight

Welcome to Valuabl - a fortnightly newsletter for value investors with investment research, stock valuations, and deep dives into my best ideas.

In Today’s Issue:

Welcome To Valuabl 2022 (2 minutes)

The Cost of Capital: January 2022 (2 minutes)

It’s A Risky World Out There (4 minutes)

Deep Dive Into My Best Idea (12 minutes)

1/ Welcome To Valuabl 2022

I hope you had an enjoyable Christmas and New Year wherever you are. Welcome back to Valuabl for another year.

On a personal note, almost everyone I know got Omicron’d in the lead up to Christmas, so festivities here in London were quiet.

Some admin to start the New Year:

If you have any feedback—if there is anything you would like to see more or less of—please reply to this email.

I am slowly working on turning my housing market research into a book. Please get in touch if you would like to contribute stories, anecdotes, ideas, or research.

If you own or operate a small business and are looking for capital or to sell part of it, I am interested in pursuing more private deals this year. If you have audited accounts and terms, I can give you a yes/no answer within a few days.

Valuabl’s readership is multiplying. You probably don’t realise it, but you are part of an elite group of fund managers, private investors, executives, and even some politicians now. Some of you reached out and have invested in my fund—I am flattered—but, for the foreseeable future, I will not be admitting new partners. However, I may look at building out a small team and providing private capital raising services (with investment opportunities only accessible to members) at some stage this year. We have a phenomenal network of intelligent, patient, well capitalised, value-oriented individuals.

Finally, the membership price will be going up at some stage this year. The current annual price is £499 for 26 issues of Valuabl. Subscribe now and lock in the current price. 2021 saw a 600% ROI for a Valuabl membership from Buy rated stocks1. Moreover, the benefit of avoiding the speculative, overvalued end of the market helped us avoid losses. See the performance of each rating class from last year.

If you are a student, get in touch, I offer a hefty discount. If you want to get a group subscription for your team at work, get in touch for a small discount.

Cheers to a great 2022.

2/ The Cost of Capital: January 2022

December was a much better month for stocks than November. The S&P500 had closed out November at 4,567.00 before finishing December at 4,766.18 for a total return of 4.36%.

The 10-year Treasury bond yield ended November at 1.456% and rose slightly to 1.512% by December 31. At the same time, my Equity Risk Premium (“ERP”) estimate for the S&P500 started the month at 4.94% and finished the month at 4.77%.

The slight increase in the risk-free rate means that investors are now pricing future money as worth slightly less than before. However, they are also pricing equities as being somewhat less risky. The net result is that the implied return on U.S. stocks has remained flat, going from 6.40% at the end of November to 6.41% at the end of December. But, with the 10-year breakeven inflation rate remaining around 2.56%, investors are still willing to realise negative annualised real USD returns.

Finally, using the average ERP of the last five years and the current Treasury yield, I value the S&P500 at 4,414—making it about 8% overvalued.

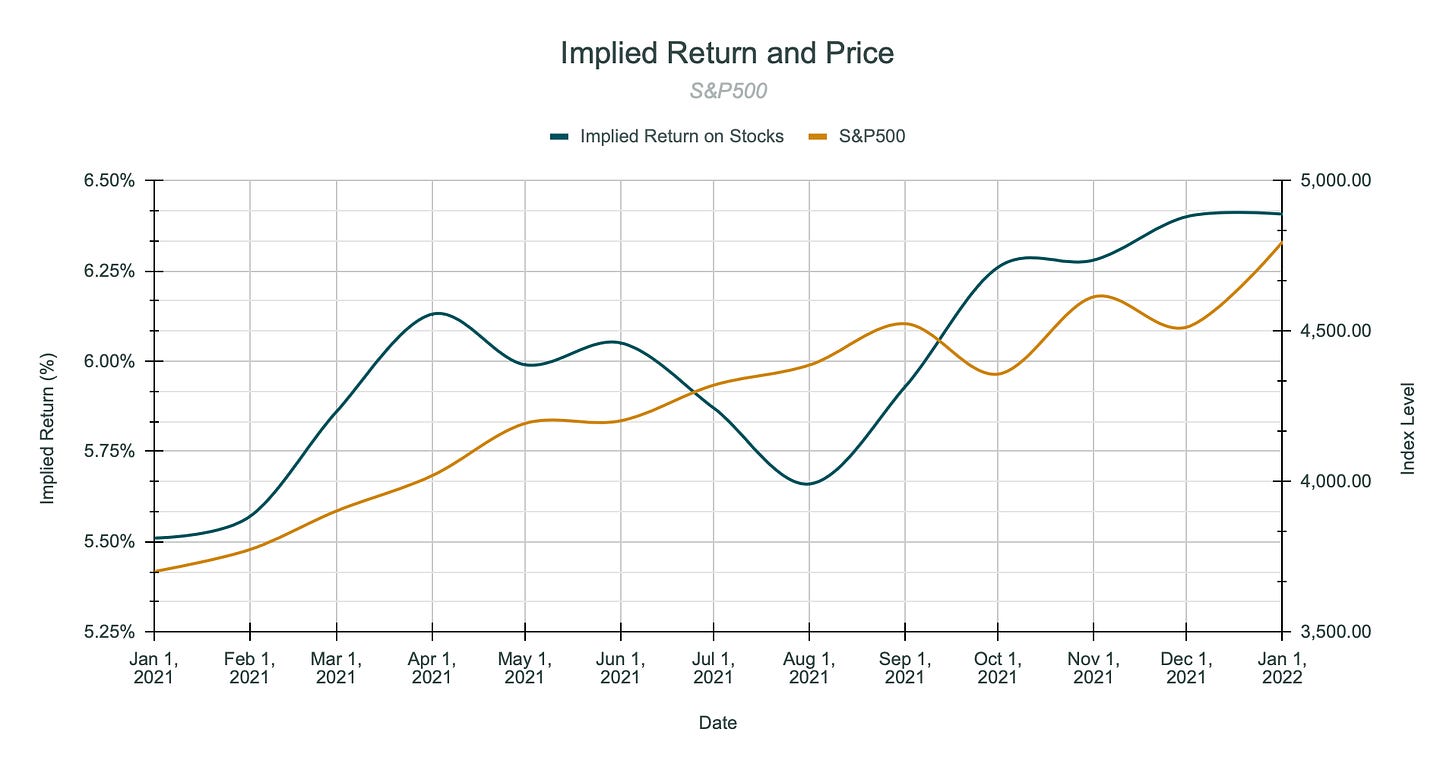

Interestingly, and almost counterintuitively, throughout 2021, the expected return on the S&P500 increased as the price level rose. Assuming the same set of cash flows, the implied return will go up if the price for the asset goes down. However, stocks don’t have a fixed set of cash flows. Expectations change and can change quickly. In the following chart, I have plotted the implied expected return on stocks (10-year Treasury yield + implied ERP) alongside the S&P500 index level.

We can see that early in the year, both rose. Then, from April until August, the implied return dropped while the index continued to rise. Since then, both have increased. At the start of the year, the implied return on stocks was 5.51%, and the S&P500 was at 3,700. By the end of the year, the implied return on stocks was 6.41% (+0.9%), and the S&P500 was at 4,797 (+1,096). This growth demonstrates how robustly corporate earnings and earning expectations have bounced back. Again, as I outlined in a previous piece, and to many people’s chagrin, I believe there is little evidence that we are in a broad-based stock market bubble.

3/ It’s A Risky World Out There

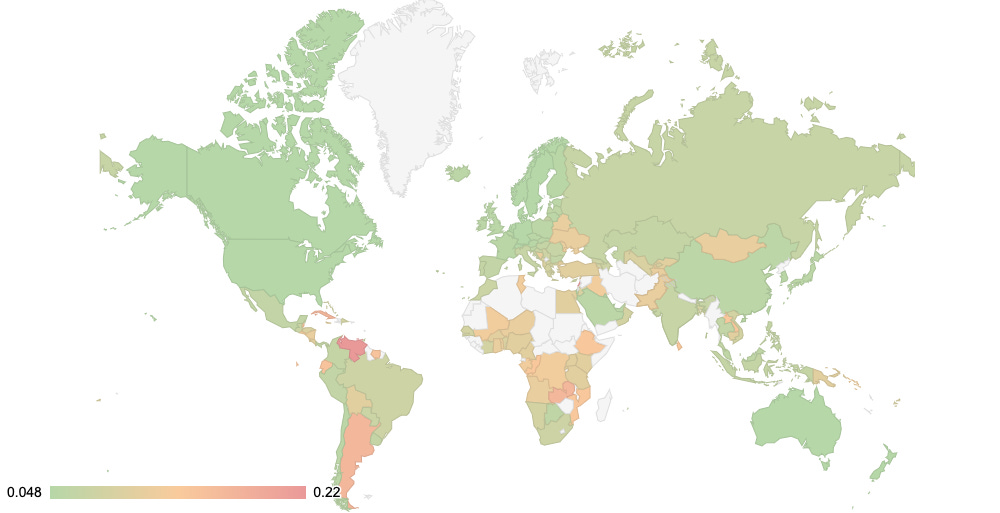

As part of my process, I update my country and equity risk premiums across the world twice a year. In the following geo-chart, I have colour coded the equity risk premium for each of the 156 countries I analyse. These premiums range from 4.77% at the safest end to 22.01% at the riskiest end.

At the Aaa/AAA rated end of things, we have countries such as Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland, and The United States. Whereas at the other end, we have countries with ratings of Caa2/CCC and below, such as Ethiopia, Sri Lanka, Congo, Laos, Mozambique, Belize, Ecuador, Suriname, Cuba, Argentina, Zambia, Lebanon, and Venezuela.

There were rating downgrades in 22 countries, with the most significant (>2 grades) downgrades being for Ras Al Khaimah, Guernsey, Jersey, Curacao, Ethiopia, St. Maarten, Tunisia, and Cuba. While, on the other hand, there were only nine upgrades: Lithuania, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Portugal, Cyprus, Serbia, Benin, Angola, and Andorra.

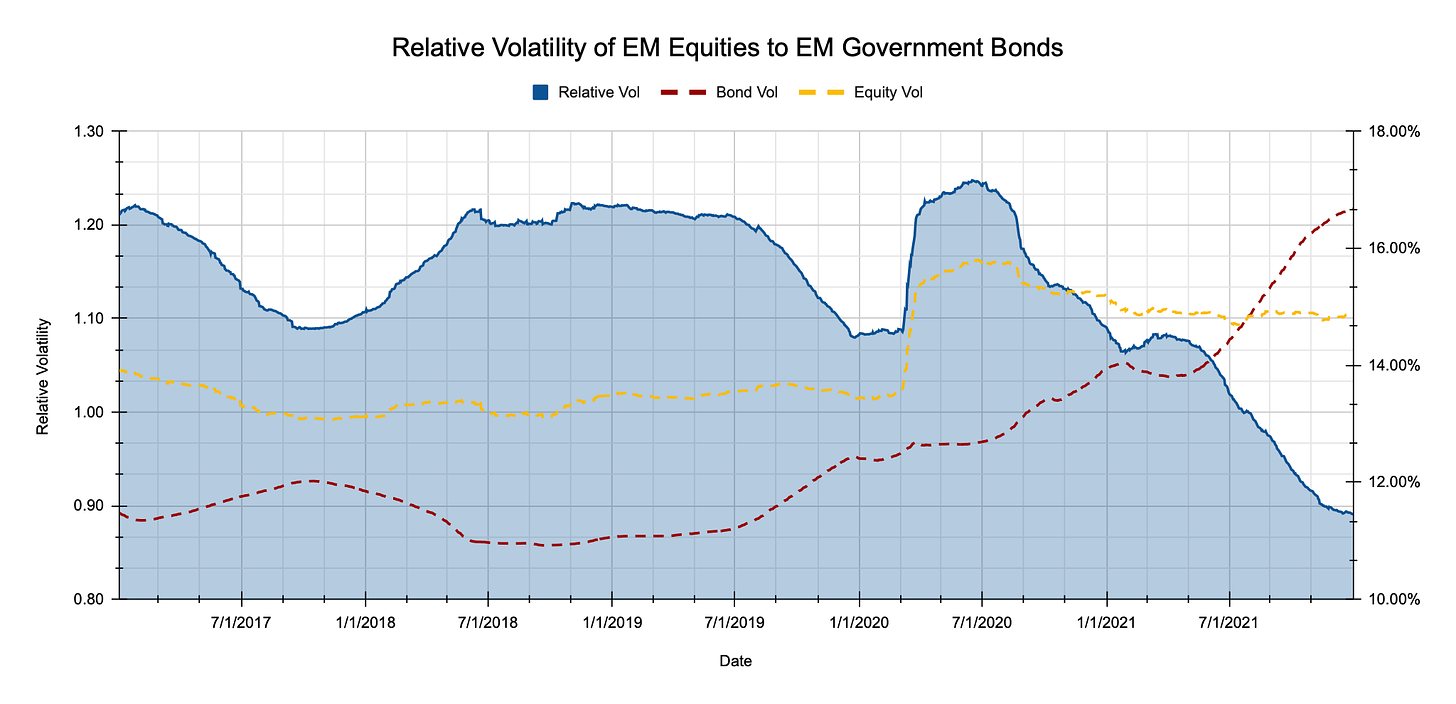

These results, so far, are pretty standard stuff. However, in August last year, something remarkable happened: Emerging Market Government bonds became more volatile than Emerging Market equities.

This volatility hierarchy reversal is a truly remarkable result. It suggests that investors are, on average, pricing the returns from government bonds in Emerging Markets as more uncertain than the returns from equities. How is this possible? Well, theoretically, it’s not. Equity will always be riskier and have more significant uncertainty and volatility than debt because it is further down the cash-flow waterfall. Going from corporates to governments amplifies this gap further. However, these are market measures that reflect the demand-supply structure and shifts of markets rather than hard-and-fast fundamentals and is an excellent example of one of the problems with only using volatility to estimate risk—you can arrive at impossible scenarios. However, we shouldn’t throw the baby out with the bathwater as there are a couple of signals that we can pull out of this:

First, investors expect government bond default rates across Emerging Markets to rise compared to corporate collapse rates.

Second, the path of rate rises and inflation is increasingly uncertain across Emerging Markets, and investors expect companies to weather the storm better than governments.2

The first signal fits with the general downgrading (22 downgrades, nine upgrades) that we saw across the globe over the last six months and the increased implied default risk. Often, people underestimate the likelihood of government default. After all, if the government can print money3 or raise taxes to pay its debts, why would it ever default? However, it does happen, and since 1960, 147 governments have defaulted on their obligations.

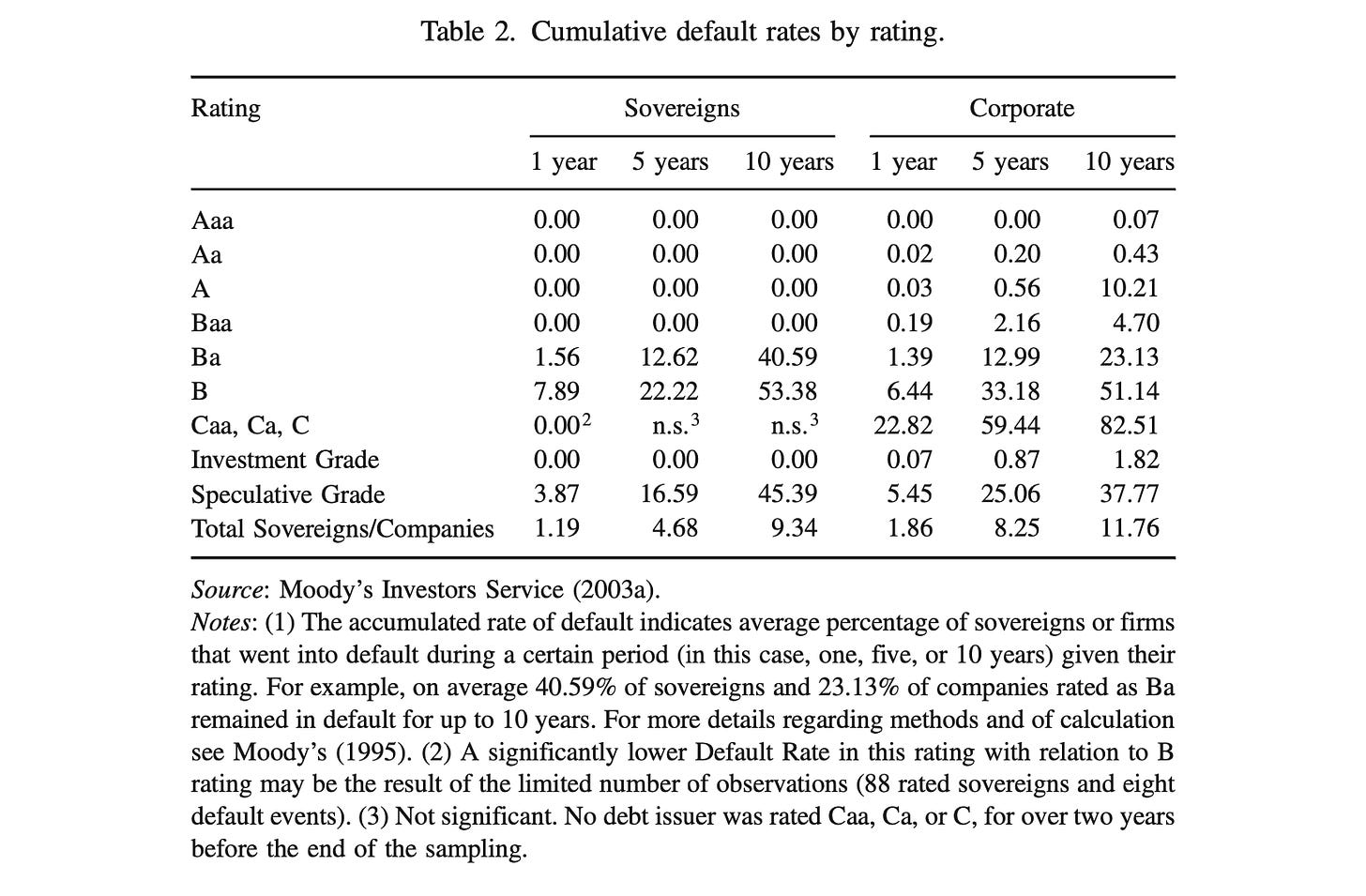

The following is a sovereign (and corporate) default table based on Moody’s ratings. It is from 2003, but it serves to illustrate the point that as countries credit ratings become more speculative, their likelihood of default increases dramatically.

The second signal fits with the dramatic increase in inflation and the uncertainty surrounding central bankers and governments responses to this. In the following chart, I plot Emerging Market Government bond volatility alongside the average inflation rate across the five largest Emerging Market economies. We can see a clear pattern.

However, rising inflation wouldn’t necessarily drive bond volatility up. The uncertainty surrounding the monetary and fiscal policy choices these countries will make to combat it is likely driving this up. With Emerging Market countries like Argentina, Brazil, Turkey, Mexico and Russia all battling against dramatic inflation rates, their mixed and flaccid responses, willingness to ignore inflation for years, or even attempts to raise effective interest rates by stealth only adds fuel to the fire of uncertainty.

What does this mean for intrinsic valuations? It means that the spread between the debt and equity country risk has disappeared for the time I’ve ever seen. Investors are, at the moment, not expecting a more significant country based spread for holding equities over local government debt. Further, ceteris paribus, it suggests that the gap between the cost of equity and the cost of debt has decreased, which makes raising equity slightly more attractive for companies and increases the average value of equities.

Truly remarkable times for the cost of capital.

4/ Deep Dive Into My Best Idea

Initially, I was working on a valuation of Hunter Douglas Group, a Dutch company making window blinds and coverings. When I first began studying the business around Christmas time, the stock was trading at €95. A preliminary valuation suggested it was worth €150-170. This gap seems like a decent opportunity and worth a deep dive, right? However, this is a story of disappointing timing.

When I came back to finish off my work on it in the New Year, I opened the WSJ and discovered that 3G Capital had announced on NYE that they are taking a majority stake in HDG and the share price had already climbed to €172.

Cue my disappointment and frustration at leaving an 80%+ almost immediate return on the table. These mistakes don’t show up in my quarterly letters to Limited Partners or on any return statement. They’re mistakes that go unrecorded. The opportunity was there, but it slipped through my fingers.

Soul crushing!

However, there are 50,000 listed companies out there, and therefore plenty of opportunities to find mispriced stocks, so on we march.